Workforce planning

Contents

Definition

Workforce planning is The process that identifies or anticipates vacant positions and the required staffing levels and skills to ensure the retention of institutional knowledge and critical skills and competences to support future business strategies

Source: Workforce Planning for New Nuclear Power Programmes

Source: Risk Management of Knowledge Loss in Nuclear Industry Organizations

Workforce planning is Template:Workforce planning 2

Source: Comparative Analysis of Methods and Tools for Nuclear Knowledge Preservation

Source: Process oriented knowledge management

Workforce planning is Template:Workforce planning 3

Source: Planning and Execution of Knowledge Management Assist Missions for Nuclear Organizations

Summary

One paragaph summary which summarises the main ideas of the article.

Description

This information addresses potential gaps between current and projected workforce needs. It takes into account diversity and labor costs and so becomes a part of the staffing plan in an organization’s business plan. It includes attrition data, planned retirements, vacant positions, development plans, succession plans, and current workforce requirements. See Attrition, Institutional knowledge and Succession planning.

Source: Planning and Execution of Knowledge Management Assist Missions for Nuclear Organizations

Description

Overall approach

National recruitment processes and practices vary from country to country and may have a significant impact on the workforce planning process. However, nuclear energy programmes require staff of the highest calibre, and it is common practice for educational and/or qualification/licensing requirements to specified by the regulatory body, at least for certain safety related roles. It may therefore be necessary to implement a specific process for the recruitment of staff. Depending on the national education capability, some organizations are able to recruit their professional talent directly at the graduate level by a competitive process that may result in several hundred candidates applying for one or more jobs. This then requires screening to select perhaps 6–10 candidates for interview, which is a time consuming and resource intensive process. At the other extreme, some countries establish nuclear ‘academies’ or universities and select students directly from secondary education with the expectation that the vast majority of ‘graduates’ from these establishments will be employed directly by the industry, thereby simplifying the ‘recruitment’ process.

It is good practice to set limits on the duration of the recruitment process, from the announcement of a job opportunity to the day of appointment. This might be days or months, depending on whether the job is at a support staff or professional level, but it sets expectations on the part of both the recruiting organization and the applicants.

Another important consideration related to the duration of the recruitment process is the scope and duration of any job related training considered necessary prior to an individual’s being authorized to undertake his or her allocated duties. This may range from a few weeks of familiarization for an experienced technical specialist working narrowly within his or her field to several years for a plant operator who may only have secondary education level qualifications.

Hence, for some positions (e.g. operations, reactor engineering, radiological safety and training), it will be necessary to begin the recruitment process several years prior to the individual’s being needed to undertake his or her duties, even prior to signing the contract for the plant.

In an area where several Member States are considering implementing a nuclear energy programme, one practical approach might be to establish a regional training centre (RTC), thus sharing the burden as well as the benefits of specialist nuclear training among several Member States. There are a number of potential benefits in developing an RTC, including:

- Set-up as well as running costs are shared between several Member States.

- An RTC avoids competition between individual Member States in trying to attract scarce specialist resources to provide nuclear training.

- RTCs are more likely to attract the support of international organizations, such as the IAEA, and are more likely to be able to establish links/partnerships with other international training/educational institutions, operating organizations and suppliers.

- Member States may be less likely to lose staff to neighbouring countries if the whole region has adequate access to such specialist training resources.

Such RTCs where staff can receive training would be particularly beneficial during the early phases of a nuclear energy programme, before there is an operating NPP or even an NPP construction project.

An essential element of developing competence is the need to gain practical training and experience. Some elements of this are discussed in the next section, but, inevitably, it will be necessary to find a means of placing some personnel within existing nuclear operating organizations. The existence of an RTC and the possibility of such a facility establishing international links may also be of benefit in this respect.

Phase 1

The initial resourcing of Phase 1 presents a major challenge in workforce planning, as a Member State is unlikely to have all or even many of the needed competencies, particularly those relating to nuclear power. Even starting with a zero baseline, the staff required for Phase 2 will have had the opportunity to develop their initial competence during Phase 1, and similarly for Phase 3. Hence, building competence during Phase 1 is vital for the success of the subsequent phases. An essential component of building that competence is giving staff real experience at the earliest possible opportunity.

One way of providing staff with the opportunity to gain experience during Phase 1 is to adopt a combined approach of importing international expertise to support the overall programme, while at the same time placing national staff overseas to gain experience. This approach may usefully be adopted by all responsible organizations: the NEPIO, regulatory body, operating organization, national industrial organizations hoping to participate in the manufacturing and/or construction of the plant, academic institutions involved in the development of national capability in the medium to long term, and those scientific/research and technical support organizations which may provide services to the plant throughout its life cycle.

External expertise has been successfully used in a number of different ways, for example:

- Contracting out whole work packages to experienced consultants, but including requirements to utilize/train national staff in delivering the work package (where little or no national competence exists in the particular area);

- Contracting with consultants to become ‘temporary’ staff working with nationals to deliver work packages, adding value in the more complex areas while developing national staff (where a modest level of competence exists);

- Engaging senior consultants to ‘coach’ national staff in specific areas of competence (where a higher level of national capability exists);

- Organizing national conferences/workshops where vendors and specialist support organizations can present their capabilities and services (care needs to be taken to ensure that no suggestion of preference or commitment to future business is implied).

Similarly, there are a variety of ways in which staff can be given the opportunity to build competence and experience overseas:

- Establishing bilateral and multilateral relationships with governments, regulatory agencies, vendors, utilities, educational institutions and others, which allow for placements and staff ‘swapping’;

- IAEA training courses, fellowships and internships;

- Formal courses of overseas study (e.g. vocational, undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, which may include industry assignments) and training (directly with utilities/national nuclear training organizations);

- Building staff training and development assignments into potential contracts with vendors, consultants, service providers, etc.;

- Developing ‘strategic alliances’ with vendors/equipment suppliers whereby national organizations obtain licenses to manufacture components in-country, which can include training and qualification in the country of origin.

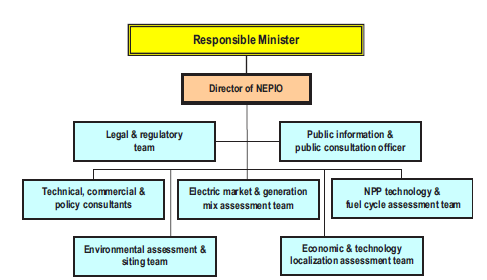

Fortunately, the number of staff directly involved in Phase 1 is relatively small, maybe only 20–30 people, although this number would require the additional support of expert groups, either nationally or internationally. Most, if not all, of these staff will be within the NEPIO, and these staff are likely to be heavily supported by national/international expertise. An example of how this group might be organized is illustrated in Fig. 4.

If a Member State has an existing regulatory body for non-energy applications, this group can be used to undertake the initial work relating to the establishment/revision of legal and regulatory requirements for nuclear energy during Phase 1, even if a separate regulatory body for nuclear energy is to be established in due course.

While it may be difficult to make any long term staffing decisions prior to a formal decision on whether to proceed with a nuclear energy programme at Milestone 1, due to the constraints of the recruitment and training requirements described above, consideration should be given to commencing recruitment of some key staff during Phase 1, to be available for work in Phase 2.

Phase 2

This will be a very busy and diverse period in terms of workforce planning and staff recruitment, and so it is easier to address each of the three main groupings separately.

Nepio

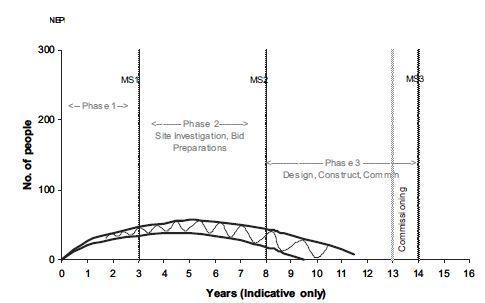

The staffing of the NEPIO will peak during this phase, as can be seen in Fig. 5, typically in the range on 20–50 staff members, depending of the level of specialist support available. By the end of Phase 2, many of their responsibilities should have been transferred to the other responsible organizations, especially the regulatory body and the operating organization. Depending on the size of the nuclear energy programme, the NEPIO may cease to exist as such (or its role may shift to one of purely coordination), with some of its oversight responsibilities (and resources) being transferred to the appropriate regulatory agencies and others being placed within those government departments which would normally be responsible for such activities. In addition, based on the experience they have gained, key NEPIO staff may be transferred into senior positions in the operating organization, either within the nuclear plant management structure (single NPP) or in the corporate organization (multi-unit programme). It is important however that, even if the NEPIO ceases to exist as an organization, the government continues to demonstrate its commitment to, and support for, the nuclear energy programme, and that key individuals within the appropriate government departments have the authority and responsibility to continue promoting the programme.

Regulatory body

The development of the work processes, human resources and competencies of the independent regulatory body is a high priority task in Phase 2 and will continue through Phase 3. During Phase 2, the regulatory body will be proposing and promulgating safety regulations and guides, as well as adopting appropriate industrial codes to properly cover all foreseen nuclear activities.

The number of staff of the regulatory body will depend on two key factors:

- The number of organizations available to provide technical support to the regulatory body (Section 2.2);

- The regulatory approach adopted by the Member State (Section 2.4).

Typically, the regulatory body may have a core staff of about 40–60 people with the competencies to develop or adopt safety regulations, develop and implement an authorization process, review and assess the safety and design documentation provided by the operating organization against the adopted regulations, and inspect the facility, the vendor and manufacturers of safety related components.

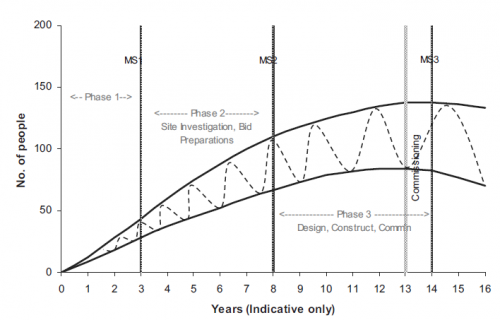

Peak numbers within the regulatory body may be higher, for example, up to 100–150 personnel, again dependent on the level of specialist independent support available and on the number of NPPs planned (workload). In the case of only one plant, these numbers should decline over commissioning, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

It is generally accepted that regulatory bodies should have competencies in four main areas:

- Legal basis and regulatory processes;

- Technical disciplines;

- Regulatory practices;

- Personal and interpersonal competencies.

Detailed guidance on the development of these competencies for regulatory body staff may be found in Ref. [11], and the IAEA can provide assistance in this area.

Operating organisation

Purely from an operational point of view, the planning and recruitment of the staff that will eventually operate the plant needs careful consideration at an early stage in the programme for the following reasons:

- The number of staff required is much larger than for the other organizations, typically in the range of 500–1000 for a single or twin unit plant, up to several thousand for a multiple unit plant (see Section 5.4).

- Many of the operating organization staff have safety related roles as described above, requiring authorization, and hence have significant training programmes, required up to several years for completion (much of such training may be initially conducted at reference plant(s) overseas).

- The commissioning of an NPP, especially if it is a country’s first plant, presents a unique opportunity for staff to gain practical experience. For those staff with specific responsibilities during the commissioning phase, their initial training must be completed. For other staff who do not have specific responsibilities, the commissioning phase still provides opportunities to observe activities and gain practical experience. For these

staff to gain maximum benefit and to avoid resource conflict, at least initial classroom training should be completed prior to the main commissioning phase. The IAEA publication Commissioning of Nuclear Power Plants: Training and Human Resource Considerations [12] provides guidance in this area.

In addition, for a first NPP, there are many other activities to be carried out by the future operating organization, such as:

- Preparing the BIS;

- Preparing the environmental impact assessment report (EIAR);

- Establishing interfaces with the various national and international bodies associated with safeguards, security, physical protection, the nuclear fuel cycle and radioactive waste;

- Establishing the integrated management system needed to ensure the safe operation of the plant;

- Creating the foundations of an appropriate safety culture prior to commencing construction;

- Preparing a strategy for dealing with the public;

- Starting to prepare emergency plans and procedures;

- Other (see Ref. [3]).

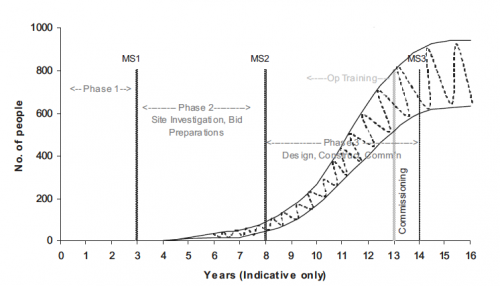

In order to ensure that there are enough competent staff available for these activities, it will be necessary to begin the recruitment and training of operating organization staff early in Phase 2 (see Fig. 7).

Phase 3

By the beginning of Phase 3, the majority of NEPIO staff is likely to have either transferred to one of the other responsible organizations or returned to one of the government departments with ongoing responsibility for the nuclear energy programme. The majority of regulatory body staff should be in place, undertaking training and discharging their responsibilities in respect of the licensing process.

A project team should be established within the operating organization and fully staffed and competent to meet its responsibilities. This team will oversee the project on behalf of the Member State/operating organization, as distinct from the vendor established project management team (PMT), which will manage the actual construction of the NPP and which may include representatives of the operating organization [3]. It is recommended that this team is part of the operating organization in order to retain their experience and expertise, although different practices may be found in different countries. This also depends on the size of the nuclear energy programme. A key issue here is to ensure that senior PMT staff are not also designated to be senior plant operations staff, as their project management responsibilities during commissioning are likely to conflict with the opportunities for operations staff to gain unique hands-on experience during the commissioning phase.

Plant staff

During this phase, the majority of the plant operating staff, especially technical staff, should be recruited and fully trained. In reality, the actual staff numbers required will vary from plant to plant. This is even true in Member States currently operating many NPPs. This can be for a variety of reasons, including:

- Stand-alone NPP or part of a fleet of NPPs with one operating organization and entralized support functions;

- Regulatory requirements specified by the Member State’s national nuclear regulator;

- Regulatory requirements specified within the Member State by provincial regulators;

- Minor differences in design, even on twin/multi-unit sites;

- Concept of operations, including the level of plant automation and control, and approach to maintenance (in-house staff, joint maintenance by operating utility staff or external contractors);

- Physical attributes of the NPP — physical layout of plant systems/equipment;

- Local labour conditions;

- National/local laws/regulations on labour and employment practices;

- Support relationships with vendors/suppliers.

To give readers of this publication a better understanding of the staffing needed by the end of Phase 3 for the operating organization (the largest of the nuclear organizations to be established), Appendix I provides an example of the median staffing levels by function for some 67 one-unit and two-unit NPPs in operation in North America and western Europe (see notes in the appendix), giving totals of approximately 700 for a single unit plant and 1000 for a twin unit. A description of each of the functions is included in Appendix II for clarity. It must be emphasized that these figures are presented as examples only, as actual numbers will depend on many factors, including those listed above.

It should be emphasized that these numbers relate to direct plant staff only. If more than one NPP is to be built, it is likely that a central or ‘headquarters’ function will be established with its own resource requirements, which in turn may impact the numbers required on each unit if some of the functions are centralized (e.g. design authority, technical support, maintenance, finance, procurement). Additional comparative data on staffing numbers can be found in Ref. [15].

The phasing of recruitment of plant staff depends greatly on their training lead times (how long they need for formal training prior to authorization/certification for their duties), and these vary greatly, depending on their roles and responsibilities. Figure 7 provides an example of the phasing of recruitment in years before commissioning, based on the totals given above. An example breakdown of qualification and training requirements (including typical training lead times, based on the stated expected entry-level education requirements) for various functions at a typical US NPP is included in Appendix III. The reader is cautioned that such lead times will vary considerably based upon national norms and regulations regarding factors such as education, vocational training, labour laws and practices, and industry practices. This variability underlines the need for each country to analyse its own situation and needs through its detailed workforce planning.

In terms of staffing a first nuclear plant, a number of options have been used, including:

- Initial operation by a national staff, which is already trained by the vendor but under the supervision of an experienced vendor supplied staff for an initial period;

- An initial period of operation staffed by the turnkey contractor’s staff while training the main body of the national staff, with a subsequent formal handover to the operating organization after a period of one to three years;

- A mixture of experienced and newly trained staff in appropriate positions (e.g. for early Chinese NPPs, approximately one-third of the staff were taken from other plants, one-third from research reactors and one-third from their ‘nuclear’ university).

Post-phase 3 (operations, decommissioning)

The completion of commissioning of the NPP marks the beginning of what should be, by current norms, a 40–60 year operating phase, followed eventually by decommissioning. Throughout this period of operations, specialist support (including research and development) will be needed for a variety of activities, for example:

- Periodic routine maintenance;

- In-service inspection (ISI) and other non-destructive testing (NDT) activities;

- Refurbishment/replacement of obsolete systems/components;

- Upgrading of reactor/turbine power output;

- Development of the case and implementation of the necessary enhancements to extend the operating life of the plant (life extension).

The same can also be said for the decommissioning phase of the NPP. While the vendor and/or other specialist external contractors already exist to provide such support, and the timescales for the development of such national capability are longer, decisions need to be taken at an early stage concerning the extent of desired national involvement in these activities in order to build any requirements into the national workforce plan and contract tender requirements as appropriate. Some aspects of this are discussed in more detail in the next section.

Source: Workforce Planning for New Nuclear Power Programmes

References

[11] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Training the Staff of the Regulatory Body for Nuclear Facilities: A Competency Framework, IAEA-TECDOC-1254, IAEA, Vienna (2001).

[12] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Commissioning of Nuclear Power Plants: Training and Human Resource Considerations, IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NG-T-2.2, IAEA, Vienna (2008).

[3] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Initiating Nuclear Power Programmes: Responsibilities and Capabilities of Owners and Operators, IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NG-T-3.1, IAEA, Vienna (2009).

[15] INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Nuclear Power Plant Organization and Staffing for Improved Performance: Lessons Learned, IAEA-TECDOC-1052, IAEA, Vienna (1998).