Community of practice

,

,

,

,

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Summary

- 3 Description

- 4 Description

- 5 Description

- 5.1 General criteria for assessing the business maturity of CoPs;

- 5.2 Community of practice approach

- 5.3 Factors leading to formation of CoPs

- 5.4 Industry process ownership

- 5.5 Sustaining factors

- 5.6 Integration of process knowledge and collection of best practices

- 5.7 CoP list

- 5.7.1 Configuration management benchmarking group

- 5.7.2 Equipment reliability working group

- 5.7.3 Nuclear supply chain strategic leadership (NSCSL, CoP)

- 5.7.4 Nuclear information technology strategic leadership (CoP)

- 5.7.5 Nuclear asset management CoP

- 5.7.6 Nuclear information management strategic leadership (CoP)

- 5.7.7 Nuclear human resources group (CoP)

- 5.7.8 Licensing community (CoP)

- 5.7.9 Fire protection (CoP)

- 5.7.10 Work Management Working Group

- 5.8 CoP benchmarking methods

- 6 Description

- 7 Description

- 7.1 Nuclear Knowledge Management

- 7.2 Communities of Practice

- 7.3 CoPs and Knowledge Management Strategy

- 7.4 The role of online facilities in enabling CoPs

- 7.5 Typical components of online CoPs

- 7.6 Key Ingredients of Effective Communities of Practice

- 7.7 Key learning points from CoP good practice

- 7.8 Governance

- 7.9 IAEA International Communities of Practice (ICoP) for Managing Nuclear Knowledge

- 7.10 Background to the ICoP

- 7.11 International Communities of Practice and the CONNECT Platform

- 7.12 Other Nuclear Energy Networks

- 7.13 Key features of CONNECT platform that support the ICoP objectives

- 7.14 ICoP Governance

- 7.15 Conclusions and Recommendations

- 8 References

- 9 Related articles

Definition

Community of practice is/are A voluntary group of peer practitioners who share lessons learned methods and best practices in a given discipline or for specialized work. The term also refers to a networks of people who work on similar processes or in similar disciplines, and who come together to develop and share their knowledge in that field for the benefit of both themselves and their organization(s). Source: Comparative Analysis of Methods and Tools for Nuclear Knowledge Preservation

Source: Process oriented knowledge management for nuclear organizations Community of practice is Template:Community of practice 2 Source: Planning and Execution of Knowledge Management Assist Missions for Nuclear Organizations

Community of practice is/are Template:Community of practice 4 Source: Process oriented knowledge management for nuclear organizations Community of practice is/are Template:Community of practice 4 Source: [[]]

Summary

One paragraph summary which summarises the main ideas of the article.

Description

Community of practice (CoP) is a network of people who work on similar processes or in similar disciplines, and who come together to develop and share their knowledge in that field for the benefit of both themselves and their organization. The original thoughts behind the concept of a CoP are generally attributed to E. Wenger, and the techniques and benefits are described in his book [10].

CoPs are generally self-organizing and usually emerge naturally but need management commitment to get started and continue working effectively. They typically exist from the recognition of a specific need or problem and are particularly important in realising benefits in R&D organizations through increased innovation and collaboration.

A CoP provides an environment (face-to-face and/or virtual) to connect people and encourage the sharing of new ideas, developments and strategies. This environment encourages faster problem solving, cuts down on duplication of effort, and provides potentially unlimited access to expertise inside and outside the organization. Information technology now allows people to network, share and develop ideas entirely online. Virtual communities can thus help R&D organizations overcome the challenges of geographical boundaries.

Source:

Knowledge Management for Nuclear Research and Development Organizations

Description

CoP background and history;

In this Appendix the development and methods of US communities of practice (CoP) are presented covering a period of time of about 1999–2008 (see Ref. [22]). NEI originally conceived the concept of communities of practice as part of a global trend in CoPs beginning about 1999. NEI’s definition of a CoP is: An effective new organizational form, called a community of practice, has emerged that promises to capitalize on existing industry structures and expand opportunities for knowledge sharing, learning, and change management. Communities of practice are groups of people who come together to share and to learn from one another face-to-face and virtually. They are bound together by shared expertise and passion in a body of knowledge and are driven by a desire and need to share problems, experience, insights, templates, tools and best practices.

Description

A community of practice as an industry peer group of experts in a business process or sub-process defined in the SNPM. The group serves as the ‘owner’ of a particular process or sub-process, managing the solution of issues for the industry in that area. A sample of responsibilities performed or supported by a CoP is listed below: — Develop, approve and adjust process Key Performance Indicators; — Recommend adjustments to cost definitions in the SNPM; — Support and guide industry management of strategic business process issues; — Agree on and administer appropriate industry projects for their process area; — Integrate, coordinate and provide guidance to special issue group activities to gain synergies on related industry process issues; — Determine future benchmarking needs.

General criteria for assessing the business maturity of CoPs;

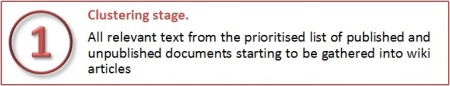

A typical community of practice has taken about six months to become chartered and operational and at about the one-year-point the organization is normally capable of developing and implementing improvement projects. Assessment of full capabilities can be determined based on the following attributes, capabilities and work products: — The formation of a leadership or steering team; — An agreed upon Community of Practice charter describing process scope, how the team will work together and their focus areas; — Publication of a documented process description, typically in ‘AP-XXX’ format containing: • Process generic steps and logic maintained in at least three hierarchical levels; • A set of definitions of industry-wide performance indicators; • A set of fully developed process cost definitions for each sub-process; — Management of a set of performance improvement projects that are coordinated with interfacing CoPs through the NAM CoP as required; — Ability to assist in the process orientation of new CoP members; — When applicable, coordinate and align the activities of related special issue groups. Achievement of all the above items has typically taken about three years. A table of CoP characteristics is summarized in Table 4.

Community of practice approach

The details concerning how CoPs appeared are best explained as part of the ‘Benchmarking loop’ discussed in article "Benchmarking"

Factors leading to formation of CoPs

Several factors are considered when considering the formation of a CoP. Foremost is the goal of identifying the most effective collection of industry professionals who can manage the business aspects of the process. They must be subject matter experts and they must be will to accept some responsibility for creating and maintaining their body of knowledge. They must also be willing to work within the system described by the SNPM to facilitate their enabling processes or process interfaces to optimize the overall business of nuclear electricity generation. Industry sponsorship is also an important factor to convince potential members of the benefits of CoPs. All CoPs were formed in one of the following ways: — An existing SIG became the CoP as a result of exposure to the benchmarking programme; — CoP was similarly formed by the adding together of one or more SIGs; — CoP was formed by like-minded subject matter experts as a result of attending a benchmarking workshop.

Industry process ownership

About 1994, INPO began a project to develop improved process descriptions for the ‘Advanced plant’ (AP). A series of the AP documents were drafted by INPO staff and reviewed by industry peer subject matter experts. These documents were envisioned to become part of a utility’s ‘Advanced Light Water Reactor (ALWR) Toolkit’. Since new nuclear plants ‘had not yet arrived’, the project was closed in 1997, but efforts continued to further develop some APs based on demand from INPO members companies. The best example of this is AP-928, INPO Work Management Process Description. Some utilities embraced the idea of improved industry process and used the AP documents series as a template starting point. Therefore some immediate benefits were achieved about 1995–1998 as this was also the time when formal NEI benchmarking projects began to provide Best Practices for consideration. Upon issuance of the SNPM Rev.0 in 1998, the concept of industry process ownership resided with INPO. However several of the ‘dormant’ APs described processes that were not part of INPO’s normal plant evaluation or assistance processes. This effectively had taken the processes ‘off the radar screen’. After taking the economic points of contact benchmarking poll in 1999, NEI worked with INPO to ‘transfer’ the following APs to NEI in 2001: — AP-902 – waste services; — AP-907 – processes and procedures; — AP-908 – materials and services. NEI was also assumed to be the industry process sponsor for all support services processes such as: — Information technology; — Business services; — Human resources; — All loss prevention processes (LP002 shared with INPO); — Nuclear fuel process. NEI began the practice of labelling industry process ownership in the SNPM, Rev.1. Ongoing involvement by CoPs offered several advantages not seen in other industries: — Knowledge management captured within: • Process description; • Key performance measures; — Integration of process steps by consensus with interfacing CoPs; and — Completion of high-value projects for the industry.

Sustaining factors

CoPs become expert managers of knowledge if, after formation, they can establish some sustaining activities that demonstrate value to the industry. There are several factors that tend to sustain these groups over time. These include: — Executive sponsorship; — Industry-level sponsorship (NEI, INPO, EPRI); — Availability of 5–7 members who are willing to be CoP leaders; — Recognized products and services; — Mentorship role for new members; — Creating value based on number of meetings and location, cost of meetings; — Achieving a balance between improvement projects established and the number of members available who are able to work on those projects, such that the total amount of work required is available from the members.

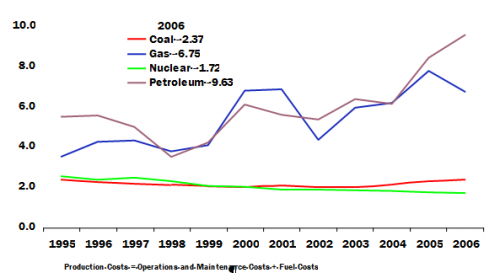

Integration of process knowledge and collection of best practices

As a result of deregulation, the benchmarking programmes and other safety and efficiency drivers, all utilities began to seek and implement best practices wherever possible beginning about 1992. Because of the large number of utility peer visits, INPO evaluations, NRC inspections and consulting engagements conducted, it is difficult to say exactly when, where and how many of these best practices occurred. However these forces were certainly aided by the INPO sharing principle and the NEI benchmarking programme. This can be seen by the overall reduction of O&M costs in progressive fashion beginning about 1997 and continuing until present day (see Fig. 23).

CoP and SIGs

In 2005, the industry conducted a thorough review of the function and value of all SIGs (including CoPs). This initiative was led by a working group of Chief Nuclear Officers with dedicated support from NEI, INPO and EPRI as required. Overall categories were established for the review and these were referred to as ‘topical areas’. The industry manager assigned to manage the review of each category was referred to as the Topical area leader (TAL). NEI 05–08 documents project results [25]. As a consequence of the TAL review, many SIGs were disbanded. Others were combined within TAL areas and several were transferred to new industry sponsorship from NEI to EPRI or INPO to EPRI, etc. This initiative is useful in understanding how changes occurred in many benchmarking areas between 2004 and 2006.

CoP list

The following CoPs were chartered by the US nuclear industry between 2000 and 2005:

Configuration management benchmarking group

The configuration management benchmarking group CoP began as a networking group in 1994 on the initiative of PPL Corp (now PPL Susquehanna, LLC). This group established a working relationship with the Nuclear Records Management Association (NIRMA) and some CMBG members participated with NIRMA in development of ANSI/NIRMA CM 1.0-2000 (see Ref. [11]). Until this time there was not complete industry agreement for what constituted ‘Configuration Management’ and INPO AP-929, Rev.0 (see Ref. [23]) was entitled Configuration Control. Following completion of the NEI Configuration Control Benchmarking Project and knowledge transfer workshop, the industry began to see how configuration management could be improved. When the CMBG became the CoP, NEI revised the SNPM configuration control process to become configuration management in alignment with the ANSI/NIRMA standard. Then the CMBG worked with INPO to revise the subject process description. In 2005, INPO issued AP-929, Rev.1, (see Ref. [24]) Configuration Management Process Description.

Equipment reliability working group

Equipment reliability became an important industry focus area about 1998, when INPO began to see adverse trends in system unplanned capability loss factor. The NEI Equipment Reliability Benchmarking Project was conducted in 2002 to help facilitate the knowledge transfer process. The project was created by mutual agreement of NEI, INPO and EPRI when it became clear that process improvement and identification of best practices in this area was necessary to address an adverse trend of systems availability at many US plants. INPO had issued AP- 913 Rev.1 Equipment Reliability Process Description, and about one-third of all plants had performed some sort of implementation. Another one-third had begun implementing in 2002 and the final third had not yet started. This was therefore decided to be a good time to conduct the project. The Equipment Reliability Working Group (ERWG) was created a few months following the knowledge transfer workshop.

Nuclear supply chain strategic leadership (NSCSL, CoP)

The NSCSL was created in 2000 following the completion of the Materials and Services Benchmarking Workshop. At the workshop, a guest speaker from NUSMG (see Section 3.5.1 below) had spoken of the benefits of an organization focused on process management of each SNPM area, using IT as the example. NEI also pointed out that there was a lack of nuclear supply chain focus at the industry level because there were several small and disconnected SIGs tapping into industry manpower for networking purposes but these groups were collectively ineffective in managing the overall business aspects of the supply chain. An industry process description was authored by a team at INPO in about 1996 but industry managers said it did not reflect current supply chain best practices and it was not actively used by the industry as a whole. An effective supply chain was also required to be a key support element of the work management process. Improvements in the work management process were continuing to the point where the supply chain process was viewed as the next essential capability for success.

Nuclear information technology strategic leadership (CoP)

The Nuclear Utility Software Management Group (NUSMG) began operating in the 1980s as a networking forum for IT professionals. NUSMG members were for the most part software quality practitioners and IT managers. As the ‘Y2K Issue’ approached, NEI successfully tapped the knowledge and infrastructure of NUSMG to assist the industry address the Y2K issue. That success further encouraged NUSMG to be involved with the NEI benchmarking programme. Also about 1998 INPO began hosting an annual meeting for IT managers where issues could also be discussed. NUSMG began considering the benefits of functioning as a CoP at the NEI/NUSMG IT Benchmarking Workshop in 2000. About the same time utility IT managers approached NEI about creating a CoP for the IT Process. IT management thought it was beneficial to remain connected with INPO, but at the same time, they wanted to be able to meet as often as required to discuss issues. They were also interested in conducting more formal benchmarking as well as specific annual improvement projects. Their vision was also to maintain an alignment with INPO, NUSMG and the SNPM. In 2001, with the assistance of INPO, NEI chartered NITSL as the CoP for process SS001.

Nuclear asset management CoP

The NAM CoP evolved in several steps beginning with EUCG in 1997. Most nuclear business managers attended EUCG and many also served as NEI economic points of contact. Since 1989, the EUCG functional cost survey had provided useful information of comparison of costs. When the SNPM was issued in 1998, EUCG began collected activity base costing data as well as SNPM KPIs. In 1999, NEI conducted the Business Services Benchmarking Project as well as initiating a new ‘NEI Business Forum’ to meet the increasing needs for discussion and industry issue activity related to deregulation, plant sales, power uprates and regulatory issues such as decommissioning costs and environmental discussions about ‘Clean air credits’. As a result NEI created a nuclear asset management task force. Initially meetings were held concurrent with EUCG. Later separate meetings were required to address NAM TF project work. Finally NAM became an NEI-sponsored CoP. In 2005, the NAM CoP was initially assigned to remain with NEI but later in 2006 it was transferred to EPRI.

Nuclear information management strategic leadership (CoP)

After seeing the results attained by other CoPs, subject matter experts (SME) in the records management process were eager to conduct an NEI benchmarking project. Most were members of NIRMA and several were part of another networking group called Document Control and Records Management. Following completion of the benchmarking project a core group of SMEs arranged with NIRMA to organize NIMSL as an NEI-sponsored CoP. NIMSL CoP is the leadership team responsible for serving as a focal point for nuclear information management activities associated with the SNPM Process SS003. Information management includes records management, document control, procedures, and office services activities. NIMSL CoP enables plants to compare their methods to others to determine efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Nuclear human resources group (CoP)

Prior to 1994, industry nuclear human resource services were available from Edison Electric Institute (EEI). In 1994, a core group of nuclear human resource professionals met to discuss fitness for duty and staffing issues in the nuclear industry. The group found it easier to create a networking and shared services group called nuclear human resources professionals (NHRP) that was later formed under EEI as a Working Committee. NHRP accomplishments included implementing the NRC Fitness for Duty Rule and benchmarking other nuclear fingerprinting, professional development, recruiting and staffing and other similar human resources and compensation/labor issues. When the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) was formed, the human resource committee was not ‘transferred’ to NEI. About the same time, INPO was monitoring and analysing total nuclear industry staffing capabilities according to a standard set of accepted professional categories. Prior to this, the utilities relied upon private consulting companies to conduct periodic NPP staffing surveys. In 1996, INPO stopped collection and analysis of staffing data which gave the Electric utility cost group (EUCG) an opportunity to add staffing data to their services offerings. A functional staffing survey was created within the EUCG in 1997. Also in 1996, the NHRP was formed outside of EEI that no longer supported nuclear efforts or committees due to the formation of NEI. The Nuclear human resource group (NHRG) was facilitated by a human resources consultant with former nuclear utility experience. In 1999, NEI began briefing the NHRP about the benefits of conducting formal benchmarking and also in working with the EUCG to establish an improved standard nuclear staffing survey and HR metrics that were in alignment with the SNPM. These planning efforts resulted in the conduct of the NEI Human Resources Benchmarking Project in 2000. After the project was complete NHRP reorganized with executive sponsorship and a more senior leadership structure to become the NHRG (CoP).

Licensing community (CoP)

NEI began about 2000 to engage the NRC strategically with a group called the License amendment task force. Both NEI and the NRC each had their own LATF and there were joint meetings conducted periodically. NEI also began conducting Licensing Information Forums in the fall about six months prior to the next NRC Regulatory Information Conference. In 2002, the NEI LATF sponsored the Licensing Benchmarking project and the industry began to engage the NRC is mutually beneficial process issues as well as the traditional regulatory discussions. Following the NEI Licensing Benchmarking Project, the formation of a Licensing CoP was discussed as part of the workshop. The following year the group was referred to as the Licensing Community and the utility portion of the LATF began to serve as a steering body for the community.

Fire protection (CoP)

The fire protection CoP was created following completion of the NEI Fire Protection Benchmarking Project and accepted in principle at the NEI Fire Protection Information Forum in 2002. This group continues to evolve as a global CoP with over 125 members spanning US and International utilities as well as other fire protection organizations. Global reach is accomplished primarily via a highly effective Web-site however direct international contacts are also maintained by formal peer visits contact and meetings at the annual Fire Protection Forum.

Work Management Working Group

The INPO Work Management Working Group is long-standing organization that over the years has acted to create and improve the work management process, develop and update AP-928, the Work Management Process Description and also to facilitate discussions between work management professionals and other utility staff such as maintenance managers, outage managers and maintenance planning managers. Work management is the centerpiece of the SNPM due to the amount of resources required to maintain plant equipment, the importance of limiting maintenance back-log and the number of process interfaces required for efficient operation. INPO has long recognized this and by 2000 the early series of four sub-process AP-documents had all been consolidated into AP-928, Rev.0. At this point, the WMWG developed a White Paper about the advantages of being better ‘Asset managers’. By collaborating with NEI, the NEI work management role in Nuclear Asset Management Benchmarking Project was completed in 2003. The WMWG also issued Rev.1 to AP-928 and was recognized as the WM CoP. In 2007, the WMWG released AP-928, Rev.2.

CoP benchmarking methods

‘Benchmarking’ activities carried out by each CoP varied from group to group. Each group was characterized by a charter, leadership structure and membership requirements. All CoPs had access to at least one Web-site for communications, posting of information and conducting business. A wide variety of CoP benchmarking activities are summarized in Table 4 below. Each CoP may choose what type of activities are best to perform based on the maturity of the overall process, industry issues that may be challenging the process and the amount of resources they have available to conduct their business.

Source: Process oriented knowledge management for nuclear organizations

Description

Communities of practice may be created formally or informally, and they can interact online or in person. In a less-formal context, they are sometimes referred to as Communities of interest. An example in the nuclear industry is the Nuclear Energy Institute’s Community of Practice.

Source: Planning and Execution of Knowledge Management Assist Missions for Nuclear Organizations

Description

Nuclear Knowledge Management

For the purposes of this document the definition for nuclear knowledge management (NKM) from the IAEA is as follows:-

"An integrated, systematic approach applied to all stages of the nuclear knowledge cycle, including knowledge identification, acquisition, utilization, sharing, preservation, and dissemination."

Communities of Practice

Within the KM literature there are numerous definitions for CoPs, but most definitions highlight the features first set out by Etiene Wenger the originator of the concept of Communities of Practice, along with anthropologist Jean Lave, defined the term Communities of Practice as:-

"Groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly."[1]

In a further text Wenger and others go on to describe CoPs as:-

"an informal group of peers, sharing ideas, insight, information and help about a topic they are deeply, sometimes passionately, interested in." [2]

Wenger elaborates that CoPs have three essential characteristics: a knowledge domain; secondly a community of people who care about the domain be it through a shared set of problems or desire to learn; and thirdly a shared practice that is documented and shared within the community, including policies, operating principles and reference documents. Wenger [3] also distinguishes CoPs from other forms of organisational collaborative groups, such as formal working groups and project teams. The essence of CoPs is that their purpose is around developing the capabilities of, and exchanging knowledge between, its members; a membership which is self-selected or voluntary.

Emphasising the informal nature of CoPs McDermott notes that:-

"membership of is often voluntary and, as community members share ideas and information, they deepen their knowledge of each other as they increase their knowledge of the topic and sense of connection." [4]

Others have distinguished 3 broad classes of CoP [5]:

- A community of learners

- A collaborative group within an organisation;

- A ’virtual’ (online) community.

CoPs and Knowledge Management Strategy

Whilst their development and use is not exclusive to the world of business, CoPs have become a key element within the KM strategies of across many industrial and commercial sectors and organisations. In those organisations, a proactive approach to enabling the formation and maintenance of CoPs has demonstrated a number of benefits that support effective knowledge sharing.

In particular CoPs can support key strategic objectives, such as:-

- Providing greater visibility and access to key domain experts in order to address short and long term technical and business issues.

- Development, across geographically distributed networks, of groups for the purpose of enhanced knowledge sharing and collaboration.

- Supporting professional career development, education, training and mentoring programmes

- Providing a mechanism for long term knowledge retention and transfer.

- Providing a mechanism and process for the capture and sharing of lessons from operational experience.

In the context of the objectives set out above, CoPs can, for example, be seen as providing valuable environments in:-

- Finding specific expertise.

- Providing a forum for ad hoc requests for information, solutions to problems, troubleshooting and operational feedback.

- Enabling collaborative development of guidance, procedures and training material.

- Supporting the sharing of experiences and learning in the development and use of methods techniques, and technologies.

- Supporting the identification and implementation of technical and safety related process improvements.

- Facilitating learning and knowledge sharing across supply chains.

In summary, CoPs can provide benefits to organisations and to individuals. CoPs provide organisations with the opportunity to leverage their knowledge networks and knowledge assets through a mechanism that does not rely on a centralised, hierarchical organisational structure for transferring knowledge. Individuals on the other hand are motivated to participate in CoPs as a means of supporting their own professional development and their professional identity.

The role of online facilities in enabling CoPs

Whilst CoP’s, as described by the definitions set out earlier in this document do not necessarily need to be mediated through online (i.e., computer-based) communication, it is a fact that some degree of online support is now a common feature of many CoPs. This is due, in part, to the opportunity afforded by the Internet to leverage knowledge sharing and collaboration across an ever wider, geographically distributed membership.

Greater accessibility to the internet, combined with greater bandwidth, ever more sophisticated tools, and familiarity with email and social media has all led to greater availability, usability and familiarity with electronic communication and interaction.

Given the regional and global nature of many communities, ’face-to-face’ communication and interaction between members is not always feasible due to economic or logistical constraints. However, the importance of a degree of face-to-face interaction has been shown to be important in the formation of communities, particularly in respect of building the requisite level of trust and rapport to ensure effective and sustained knowledge sharing between key members.

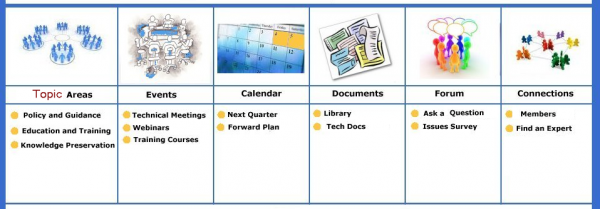

Typical components of online CoPs

There are certain features and facilities that characterise many online supported communities, namely:-

- A searchable directory of member profiles detailing for example contact details, areas of expertise and areas of interest.

- Forums for submitting and responding to ’ad hoc’ requests for advice and support from community members, or for managing discussions and collaboration on particular thematic topics that are of interest to a sub-set of the community.

- ’Blog’ facilities to communicate and prompt discussion on key topics of interest.

- Document management facilities for storing and retrieving documentation key to the knowledge domain such as guides, standards and lessons learned.

- Collaborative work spaces (e.g. ’Wikis’) to support the development amongst the community of new material such as procedures, guides and training courses.

- Calendar of Events informing members of online and face-to-face seminars, webinars and conferences.

Figure 1. below, presents a ’wireframe view’ of a Home Page of an online CoP.

Key Ingredients of Effective Communities of Practice

Key learning points from CoP good practice

The basic elements that underpin effective, proactive and sustained CoPs include clear objectives and purpose; a clearly understood and motivated membership; an available, accessible and user friendly online platform; and effort available for defined and resourced roles to support the running of the network.

The increased use of CoPs within organisations’ KM strategy has prompted several benchmarking studies and ’good practice’ reviews (e.g. [6], [7]). These studies have sought to identify what makes effective CoPs, and conversely what the challenges are to implementing and sustaining active CoPs.

The KM literature contains many examples of reviews of the critical factors that underpin successful CoPs (e.g., [5], [6], [7]). Such factors include, but are not limited to:

- A clear rationale and link between a CoP and the needs of the members of and participating organisation, or organisations.

- Senior management, or key stakeholder sponsorship to ’permission’ and encourage network participation.

- A clear and well understood scope and purpose (by sponsors and community members)

- Clearly defined and supported roles and responsibilities for CoP leaders and facilitators along with appropriate training.

- An appropriate balance between achieving the informal and voluntary participation from community members and a degree of formal ’governance’ to ensure quality and coherence of information and knowledge exchange and sustained activity.

- A sufficient level of ’trust’ amongst CoP members to ensure an adequate level of knowledge seeking and knowledge sharing activity.

- An appropriate mix of face-to-face and online CoP activities and support

- Provision of user friendly IT tool(s) for online activities

- Measurable and monitored outcomes

The next section covers in more detail, the insights from CoP good practice regarding the necessary governance framework required to develop and sustain an effective network.

Governance

Lessons from CoP good practice has shown the importance of introducing a degree of governance which whilst it must not stifle the voluntary and active participation of members, enables community growth and ensures provision of the correct infrastructure in terms, for example, of administration, online facilities and overall coordination. Bearing the requirement to balance the informal and formal, a governance framework should set out and ensure adequate resourcing for, the appropriate controls, roles, responsibilities, processes and online tools to ensure the desired level of knowledge sharing and collaboration and to ensure that the scope and purpose of the community is sustained.

Whilst it is important to avoid negation of the positive effects of a healthy, voluntary interaction between a motivated network of experts and learners it cannot be expected that simply making a CoP available will lead to a dynamic sustainable knowledge network. A CoP needs to be stimulated into action, needs to be sustained through proactive governance and facilitated through a number of nominated roles and resourced in terms of IT provision in relation to online facilities.

As a minimum the governance framework should:-

- Guide the initial CoP definition in terms of scope and objectives.

- Ensure engagement with key stakeholders including sponsors for the CoP.

- Provide adequate resource in terms of effort for key roles and for the provision and on-going support for online platform and tools.

- Ensure ’terms of reference’ and necessary guidance (’rules’) for CoP behaviour and expectation are in place and communicated to members.

- Ensure processes are in place to monitor quality in terms of knowledge sharing and collaborative content and its appropriateness; and that overall CoP performance is monitored with regard to its specified objectives.

3.2.1. Roles and Responsibilities

Many organisations who have implemented CoPs as part of their KM policy and strategy have introduced a formal governance framework. Whist the range and details of such frameworks vary from organisation to organisation a common, minimum set of roles and responsibilities can be identified:-

Steering Group

A management team comprising key stakeholders, responsible for the development of CoP policy, promotion of CoPs as a knowledge sharing mechanism, securing of resources and monitoring of overall performance.

Sponsor

Often a senior manager who represents and promotes the CoP within the organisation and who identifies key stakeholders and key subject matter experts who should be involved in the CoP.

Coordinator or Facilitator

A subject matter expert, or a more junior employee who participates as part of their professional development, who acts as the point of contact for day to day co-ordination of the CoP.

IT Support

Usually within the IT or IS function who setup and maintain the IT tools that will underpin the online CoP facilities.

Members

To actively participate in the knowledge sharing and collaboration activities of the CoP.

3.2.2. Measuring CoP performance

It is important to define and monitor a range of measures to ensure that the CoP is continuing to meet its objectives, is engaging with community members and is not reliant on sustainability from the facilitation team or a small proportion of core members. Some exemplar measures or metrics associated with a CoP are identified in the Table 1 below.

Table 1 Indicative performance measures

| Metric | Description |

| Effectiveness | |

| Quality Measurements track the quality of CoP experience |

|

| Efficiency | |

| Usage measures Track member activity |

|

| Process Measurements track the efficiency of network processes |

|

| Economy | |

| Cost Measurements Track the overall cost of running the CoP |

|

IAEA International Communities of Practice (ICoP) for Managing Nuclear Knowledge

Background to the ICoP

So far this document has focussed upon the general objectives, knowledge sharing, expertise networking and collaborative characteristics associated with CoPs. This section now overviews some of the key efforts that the IAEA is making in facilitating international CoPs (ICoP) on behalf of, and in conjunction with the active participation of its Member States.

In this regard, the objectives of ICoP are as follows:

- To support existing activities and initiation of new activities for Member States.

- To establish, make visible, and maintain a worldwide network of accessible nuclear expertise.

- To facilitate sharing and transfer of expertise and experience in a socially responsible way through online and face-to-face meetings.

- To promote stakeholder awareness, understanding and impact of managing nuclear knowledge for the peaceful applications of nuclear technologies.

- To demonstrate the role and value of CoP as one element of an overall KM strategy.

Since 2002, the General Conference has noted the important role that the IAEA plays in assisting Member States in their efforts to preserve and enhance nuclear knowledge and to facilitate international collaboration.

To better respond to the recommendations and suggestions of Member States and the IAEA Standing Advisory Group for Nuclear Energy (SAGNE) the Agency decided to establish international communities of practice for managing nuclear knowledge.

Subsequently, several Technical and Consultative Meetings were held with participation of experts from Member States. The participants of the meetings made comments on how to develop further the IAEA activities in this area of ICoP in order to generate and accelerate knowledge sharing, as well as to increase the efficiency of supporting Member States.

In discussing the potential scope of an ICoP, emphasis was placed upon the activities, tools and culture that promote or facilitate knowledge creation, retention, utilization, storage and transfer. Discussed, in particular, were the different needs of countries that have an on-going nuclear power program, countries that face decommissioning of their nuclear power programs, those that are considering a nuclear renaissance following stagnation, and those countries with ambitions for nuclear power.

International Communities of Practice and the CONNECT Platform

It is acknowledged that there is now a potential to complement IAEA Communities of Practice by exploiting the availability of an on-line platform to create broader expertise networks and collaborative activity and to stimulate a greater level of informal knowledge exchange.

Therefore, the IAEA Department of Nuclear Energy, with the support of the Technical Cooperation program and funding from the European Commission, have embarked on the development of the on-line ’CONNECT’ collaboration platform, which utilises Microsoft Sharepoint™ technology. This collaborative platform provides and/or addresses the features that were described earlier in this document, as well as a space for accessing quality learning materials to ICoP participants.

At its launch there were 6 networks on the CONNECT platform hosted by the IAEA (with the NKM ICoP being one of those networks).

Nuclear Knowledge Management (NKM) Community of Practice

The aim of the ICoP on NKM is described below:

"To serve on behalf of IAEA Member States as an international forum for learning and growth of competence in the application of nuclear knowledge management." [8].

The Agency’s NKM programme currently covers:

- Development of methodologies and guidance documents for nuclear knowledge management;

- Facilitation of nuclear education, training and information exchange; and

- Assisting Member States in maintaining and preserving nuclear knowledge.

Radioactive Waste Management Networks

The first ICoP developed and promoted by the IAEA was in the area of high-level radioactive waste (HLW) disposal. The Underground Research Facilities Network (URF) was organised around the transfer of knowledge and sharing of research facilities for the investigation and construction of underground HLW and spent fuel repositories. Following 10 years successful operation, other ICoPs have been proposed, and currently include:

- International Decommissioning Network (IDN)

- Network of Environmental Management and Remediation (ENVIRONET)

- International Low Level Waste Disposal Network (DISPONET)

- International Network of Laboratories for Nuclear Waste Characterization (LABONET)

Other Nuclear Energy Networks

Besides the core networks comprising radioactive waste management technologies and NKM, the IAEA, due primarily to the success of these efforts, has encouraged the growth and development of ICoPs in other complementary areas. A background description of the other communities of practice on the CONNECT platform is shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Communities of Practice under the IAEA CONNECT Platform

| International Community of Practice | Background |

| Underground Research Facilities (URF) |

Under the auspices of the IAEA, nationally developed Underground Research Facilities (URFs) and associated laboratories concerned with the geological disposal of radioactive waste are being offered for use by various Member States. The URFs and laboratories form a Network for training in and demonstration of waste disposal technologies and the sharing of knowledge. These URFs and the participants in the Member States make up the Underground Research Facilities (URF) Network, a community of practice and learning for geological disposal of nuclear waste. The objectives of the URF CoP are as follows:

|

| I&C Technologies (ICT) |

Nuclear utilities are facing challenges in several I&C areas with ageing and obsolete components and equipment. With license renewals and power uprates, the long-term operation and maintenance of obsolete I&C systems may not be a cost-effective and reliable option. As a consequence, the nuclear industry modernises existing analog I&C systems to digital I&C, as well as implements new digital I&C systems in new plants. The increased functionality of the new digital I&C systems can also open up new possibilities to better support the operation and maintenance activities in the plant. The I&C CoP is one mechanism by which the IAEA can provide a setting for exchanging information in meetings and a forum to share lessons learned by producing technical documents in various technical areas. |

| Networking Nuclear Education (NNE) |

The objective of the Networking Nuclear Education (NNE) is to complement new and existing IAEA educational network activities such as the AFRANEST, ANENT and LANENT. To serve on behalf of IAEA Member States as an international forum to identify best practices and to share lessons learned experiences and resources amongst nuclear educational institutions. |

| International Decommissioning Network (IDN) |

In 2007 the IAEA launched the IDN to provide a continuing forum for the sharing of practical decommissioning experience in response to the needs expressed at the Athens Conference in Dec. 2006 on "Lessons Learned from the Decommissioning of Nuclear Facilities and the Safe Termination of Nuclear Activities". This Network is intended to bring together existing decommissioning initiatives both inside and outside the IAEA to enhance cooperation and coordination. Specifically it’s objectives are:

|

| Integrated Management Systems Network of Excellence (MSN) |

A management system is a framework for managing and continually improving an organisation’s policies, procedures and processes. The MSN CoP is focusing on the sharing of experience and experience on management systems. |

Key features of CONNECT platform that support the ICoP objectives

In addressing the objectives of the ICoP presented in the previous section, and in considering the CoP good practice earlier in this document, the key features and elements of the ICoP comprise a blend of facilitated virtual (on-line) and face-to-face interactions between the community members that:-

- Connects nuclear experts and practitioners through member profiles and experience lists.

- Collects and shares nuclear experience and good practice.

- Facilitates collaboration in order to further investigate and develop guidance on particular issues and topics being faced by the international nuclear community.

Given the international and geographically distributed nature of ICoP members there are obvious budgetary and logistical constraints with regard to the amount of face-to-face meetings that can be convened. In this way ’virtual’ interaction provides a powerful and effective means of communication between members. At the same time it is acknowledged that a purely ’anonymous’ community is unlikely to build an effective knowledge sharing network and therefore key meetings are arranged where appropriate and feasible.

The ICoP therefore, facilitates the intended uses by employing a range of IT support tools that are intuitive for the user (user friendly), and do not require any software installation. The supporting IT technologies provide the following functions:

- The ability to share information between the members of the network

- A searchable list of members available only to members of the network

- A means of finding experts, or members with a shared experience, in a particular topic

- A list of links to other networks, institutions, websites, etc.

- Basic document management facilities.

The ICoP seeks to address issues facing member states in the various areas as shown in Section 4.2. Whilst an important feature of the ICoP is its support for free-flow and informal knowledge exchanges between members, certain ’Thematic Areas’ are initiated that group together discussion and development of learning material (e.g. guides, training material) on particular topics.

As the ICoP evolves and as particular topics, issues, and stakeholder requirements arise so further Thematic Areas may be set-up to supplement or, if appropriate, replace extant Areas. The table below sets out some example topic area categories that have been identified during the course of the Technical and Consultancy meetings referred to earlier.

Table 3. Illustrative Thematic Areas

| Thematic Areas | Example sub topics |

| Methodologies and guidance |

|

| Nuclear education, training and information exchange |

|

| Knowledge maintenance and preservation |

|

ICoP Governance

Drawing once again upon CoP good practice, a governance framework has been devised to ensure more effective running of the ICoP. Such a framework describes the roles and responsibilities of the IAEA Scientific Secretaries who co-ordinate the ICoP; and participants from the Member States who may act in subject mater expert, Thematic Area facilitators or just participants in the network. A ’code of practice’ is also in place: covering aspects of content development and usage, and acceptable practices related to usage of the features and functions of the on-line tools.

In this regard, a Governance Plan has been developed to cover the range of ICoPs contained within the CONNECT platform. Table 4, below, sets out the key roles described in the ICoP Governance Plan.

'Table 4. ICoP Roles and Responsibilitie's

| Role | Responsibilities | Appointment |

| Chairperson |

|

IAEA Staff, e.g. the Scientific Secretary. This selection will be made by the IAEA |

| Coordinator |

|

IAEA staff. The selection will be made by the IAEA |

| Thematic Area Moderator |

|

IAEA staff or Member State nomination or volunteer role to be filled by a subject matter expert |

| IT support |

|

An IAEA staff member |

| Members |

|

Conclusions and Recommendations

This document has outlined the IAEA’s objectives in establishing an International Community of Practice (ICoP) on nuclear Knowledge Management (NKM). The ICoP is presented as a valuable initiative to further leverage the sharing of NKM knowledge and experience across the international community.

The ICoP initiative is designed to complement the Agency’s overarching NKM programme which comprises the following elements:

- Development of methodologies and guidance documents for nuclear knowledge management;

- Facilitation of nuclear education, training and information exchange; and

- Assisting Member States in maintaining and preserving nuclear knowledge.

In addressing its proposed objectives and in complementing the Agency’s NKM programme, the ICoP will facilitate:

- Connections between NKM experts and practitioners through member profiles and experience lists.

- Collection and sharing of NKM experience and good practice.

- Collaboration between members seeking to further investigates and develop guidance on particular issues and topics.

In defining the scope and implementation requirements of the ICoP effort has been made to draw upon wider experience of KM good practice in this area.

A key mechanism for enabling the ICoP and achievement of its objectives will be the provision of the on-line, web based, CONNECT platform. Such on-line support will be supplemented, as is feasible and desirable, by face-to-face meetings that help build an effective knowledge sharing and collaborative international community.

The ICoP programme represents an on-going initiative driven by the IAEA and being developed and refined in consultation and based upon active participation of the Member States.

References

[1] Lave, J. & Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral participation, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[2] Wenger, E., McDermott, R., Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. 2002. Harvard Business School Press.

[3] Wenger, E.C., Snyder, W.M. Communities of Practice: the Organizational Frontier. Harvard Business Review January –February 2000.

[4] McDermott, R. 2005 ‘From the Margin to the Heart of the Company: High performance Communities’ Consultancy paper.

[5] Mitchell, J.G., Wood, S.,Young, S., 2001, ‘Communities of practice: reshaping professional practice and improving organizational productivity in the Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector Reframing the Future Initiative’ .

[6] Communities of Practice (CoP) Benchmarking Report: Using CoPs to improve individual and organisational performance. 2006. Knowledge and Innovation Network (KIN) Warwick University, .U.K.

[7] ‘What are the conditions for and characteristics of effective online learning communities?’ Australian Flexible Learning Framework Quick Guides series 2005.

[8] Li, L.C., Grimshaw, J.M., Nielsen, C., Judd, M., Coyte, P.C., Graham, I.D. ‘Evolution of Wenger's concept of community of practice.’ Implementation Science. March 2009

[9] A Proposal for Establishing an International Community of Practice on Nuclear Knowledge Management (ICoP). IAEA NKM document 2010.

[10] Wenger, E., McDermott, R., Snyder, W., M., Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide To Managing Knowledge, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, USA (2002).