Educational programme

Contents

Definition

Educational programme is A set of organized and purposeful learning experiences with a minimum duration of one school-year (or academic year), usually offered in an educational institution Source: Nuclear engineering education: A competence-based approach in curricula development

Summary

One paragraph which summarises the main ideas of the article.

Description

University programmes in nuclear engineering

Engineering education has been offered for many decades along several different tracks. One approach is to have two levels in the academic education: the Bachelor’s, or undergraduate degree, based on approximately three to four years of study at the university level and a more advanced degree, the Master’s, which involves one or two years of study beyond the Bachelor’s. Another approach that has been widely used, especially in Europe, is the Diploma. It typically involves five years of study. A third approach is the Engineer degree consisting of five to six years of study. This has been the tradition in, for example, France, Russian Federation and the Ukraine. This picture is, however, changing. In June 1999, the Ministers of Education in the European Union entered into the Bologna Process (The Bologna Process is a series of ministerial meetings and agreements between European countries designed to ensure comparability in the standards and quality of higher education qualifications. Visit [1] for more details). This has led to the adoption of the Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programmes at most European universities, which replace the Diploma or the Engineer degree. France focuses the nuclear engineering education either at the Engineer degree (five years usually, six years in some instances) within its specific ‘Grandes Ecoles’ approach, or as a Master’s degree (five years) in harmony with the Bologna Process. Russian Federation is taking a two-tier approach in which the Bachelor’s/Master’s programmes will be implemented. This is a key part of the strategy for international engagement. However, the degree of Engineer will be retained in Russian Federation and Ukraine to satisfy the needs of the domestic industry.

Engineering education is country and region dependent. There is no unique model and it is important to adapt pragmatically to the educational, institutional and industrial framework. However, in this report, it is important to specify that the Bachelor’s level can be reached after three to four years, and the Master’s level requires one or two additional years. This amount of time is necessary to acquire the qualifications listed and to become a competent engineer with the required industrial background.

This report deals with the common curriculum requirements resulting from a competence- based approach for the Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in nuclear engineering, applying to all nuclear application but focusing mainly on nuclear power. The expectations of degree recipients at each level are the following:

- On completion of a Bachelor’s degree level qualification, it is expected that the student will have comprehension and knowledge of nuclear engineering systems and will be able to solve problems and determine technical solutions for real processes;

- On completion of a Master’s degree level qualification, it is expected that the student will be able to analyse, synthesize and evaluate knowledge gained, and apply this knowledge to nuclear power plant systems.

Beyond these expectations, it is further recognized that there are a set of specific outcomes that should result from the completion of the curriculum. At the Master’s degree level (or Engineer’s degree), graduates should be able to demonstrate the following:

- Identify, assess, formulate and solve complex nuclear engineering problems creatively and innovatively;

- Apply advanced mathematics, science and engineering from first principles to solve complex nuclear engineering problems;

- Design and conduct advanced investigations and experiments;

- Use appropriate advanced engineering methods, skills and tools, including those based on information technology;

- Communicate effectively and authoritatively at a professional level, both orally and in writing, with engineering audiences and the community at large, including outreach;

- Work effectively as an individual, in teams and in complex, multidisciplinary and multicultural environments;

- Have a critical awareness of, and diligent responsiveness to, the impact of nuclear engineering activity on the social, industrial and physical environment with due cognisance to public health and safety.

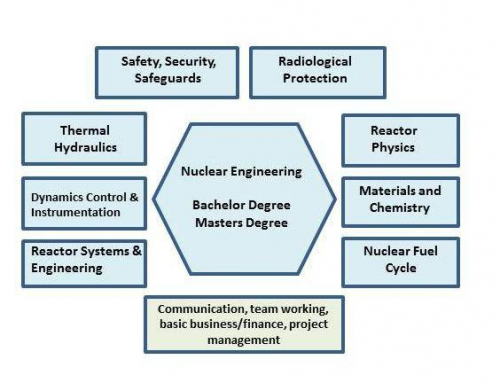

In terms of specific technical areas, the Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in nuclear engineering bring together a number of key areas that are integrated into a nuclear engineering academic degree programme. This scope is depicted in Figure 2.

The areas shown in the Figure 2 generally represent the key fields of study required to prepare a nuclear engineer for employment in a nuclear power plant. For the nuclear engineer, it is important that these topics are well integrated together to produce a well-prepared graduate who can enter into the training programmes for a specific nuclear power plant and reach the required level of competence to successfully carry out his or her responsibilities for safe, secure and economical operation.

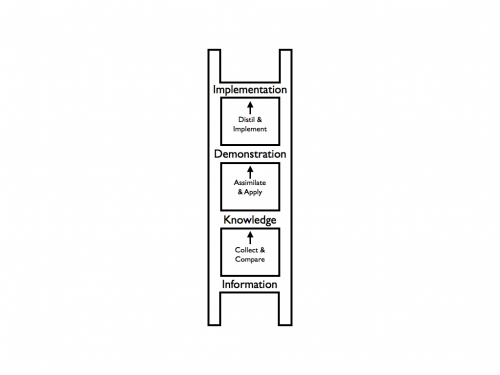

For universities developing new programmes, a more detailed description is useful. In the two following sections, the competencies are defined at both Bachelor’s and Master’s degree levels with the focus on those who will specifically be employed at nuclear power plants. In addition, requirements of the graduate are given in more detail, and involve what each student should possess: a specified level of knowledge (Knowledge), be able to demonstrate - application of the knowledge (Demonstration), and know when to implement the knowledge (Implementation). This can be represented as a ‘knowledge ladder’ (see Figure 3).

Competencies of graduates with a bachelor of nuclear engineering

Requirements for a graduate with a bachelor's degree in nuclear engineering

Competencies of graduates with a master of nuclear engineering

Requirements for a graduate with a master of nuclear engineering

Programme implementation

The development of a quality curriculum is a key to the establishment of a nuclear engineering educational programme. However, as important are the steps used to implement the programme. It is essential that these programmes are implemented by competent teaching staff, which they make good use of information and communications technologies such as e-learning tools and simulators, and that students can benefit from experimental facilities and research reactors, if available, particularly for master programmes. The curriculum should adhere to accepted international practices. It must be approved by the responsible governmental ministries and authorities. It is also essential, where possible, to involve the organizations that will be hiring the graduates. This can be done in several ways. A common ‘best practice’ is to have an ‘external’ advisory board, with membership made up of potential employers, alumni associations, governmental organizations, professional and scientific societies, research laboratories, and universities. This type of board will provide on-going input and feedback and can be very helpful in assuring the continued quality, and relevance, of the academic programme.

Additional benefits can be achieved through collaboration between universities and the nuclear industry, which is a potential employer. Internships or co-operative education experiences will add significantly value to the education of students. It provides a deeper understanding of the material being presented in courses. It also allows the students to see the expectations they will face after graduation in an industry environment. It is also very useful to have representatives from industry, government agencies and research laboratories come to the university to present talks and seminars, and to give lectures in class relating to their technical or scientific expertise.

As part of developing a nuclear engineering academic programme, it is very positive to establish a student chapter of a professional or learned society. This further expands the outlook of the students, and conveys the need for professionalism in his or her career. If it is possible, enabling students to attend professional or technical meetings, regional, national or international, adds significantly to their educational experience. International cooperation through exchanges of students and joint programmes can also contribute significantly to the education of competent nuclear engineers.

Sharing resources is a tendency and a necessity. A number of regional and national educational networks and consortia dealing with nuclear engineering education are playing important roles in sharing curricula, programmes and opportunities for students. Each of the networks has its own characteristics and is unique [8, 9]. The scope is aimed at meeting particular regional and national needs, but basic goals are similar: exchange of information, resources and best practices. In Canada, for example, the University Network of Excellence in Nuclear Engineering (UNENE) has a strong link with industry. UNENE supports, for instance, the establishment of Industrial Research Chairs at universities in Canada to strengthen academic offerings in key technical areas relating to nuclear technology. In Russian Federation, the National Research Nuclear University (NRNU MEPhI) centred on the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute brings together 23 campuses across the country. This new institution embodies all the capabilities in nuclear engineering education. In France the ‘Institut International de l’Energie Nucléaire’ (I2EN) created under the auspices of the French Council for Nuclear Education and Training, located on the Saclay campus, comprises a network of the best nuclear engineering curricula in France in particular those taught in English, and an in-house team in charge of promoting the French offer in nuclear education and training. The French nuclear industry is closely associated with this institute. In the United Kingdom, the Nuclear Technology Education Consortium (NTEC) provides a one- stop shop for a range of postgraduate education and training in Nuclear Science and Technology. Also Japan and Mexico have created recently national networks to coordinate and concentrate efforts.

In Europe, the European Nuclear Education Network (ENEN), links universities from a number of countries and helps to promote quality uniform curricula in nuclear education. They have created a European Master of Science in Nuclear Engineering (EMSNE). In Asia, Latin America and Africa, similar initiatives are under way with the sponsorship of the IAEA: the Asian Network for Education in Nuclear Technology (ANENT), the Latin America Network for Education in Nuclear Technology (LANENT) and the African Regional Cooperative Agreement – Network for Education in Nuclear Science and Technology (AFRA-NEST). They link programmes and institutions related with nuclear education in different countries promoting high quality nuclear education.

For emerging countries developing nuclear engineering educational programmes, these networks are of immense value for resources and information. A good strategy to support nuclear education efforts is to become affiliated with networks in the region.

To assure quality and to provide a framework to measure performance and improvement of nuclear engineering educational programmes, it is important to employ a set of benchmarks. These are especially useful in gauging the status of a university against the best academic programmes in the world. The benchmarks provided in Appendix I are not meant to serve as a set of formalized evaluation criteria. Instead these will allow an institution to gain insight into its own status and programmes to enable it to improve, if necessary, or maintain the highest standards. The benchmarks will also provide guidance for further development, improvement and investment of resources.

Accreditation of programmers

To assure quality and continued relevance, on-going accreditation of academic programmes is of major importance and this is carried out in a variety of ways. In some countries, the accrediting function is performed by government ministries and agencies. Elsewhere it may be handled by professional or learned societies. A third approach is to have accreditation handled by independent organizations.

Historically, accreditation approaches of academic programmes primarily focused on content. For engineering, this was based on examining the curricula to determine if sufficient attention was being given to areas including mathematics, the physical sciences, engineering sciences and design. However, over the past decade, a shift has taken place in the emphasis to include a more ‘outcomes’ based approach. The accreditation review should include assessments of the performance of a graduate in his or her role as an engineer (The review normally includes feedback from the employers of the graduates relative to their satisfaction with academic preparation and performance of the graduates). Programme outcomes may be best defined as the quality and quantity of graduates, together with the roles and impacts they have in their careers and for their employers. An effective nuclear engineering programme should engage with the organizations that employ their graduates to determine the quality of the preparation of the students for a career in industry. A well-organized link with the employing organizations provides a critical feedback that leads to continuous improvement.

A well-defined set of criteria should be developed by the accrediting organization and presented to the academic institution well in advance of an accreditation visit. This is necessary to enable the faculty/department to implement the curriculum/a needed to meet the criteria.

For creditable accreditation two features are vital:

- Educational programmes are, by their nature, long-term endeavours to graduate students over three to six year time frames. As the accreditation criteria need to be stable and have continuity the accrediting organization must establish clear and consistent criteria. They must not be continually altered, as it will dilute the quality of the educational programmes.

- The reviews must be done on a regular periodic schedule, which could be every 3-5 years. A sufficiently long period of time enables the faculty/department to implement changes and improvements, and allows the organization to properly prepare for the next review.

The following are the key elements in a well-established accreditation process:

Self-evaluation report

Based on an existing or evolving programme, the faculty or department has a process for preparation a self-evaluation report describing its capacity to deliver an educational programme in a particular technical field or discipline.

The structure of the self-evaluation report should include information on the following elements:

- Period covered by the evaluation;

- Faculty/department presentation and history;

- Accreditation procedure;

- Comparison to national (or international) standards;

- Type and duration of the proposed education programme;

- Involvement of industry in the programme development and implementation;

- Main objectives;

- General and specific competencies of the graduates.

Actions to attract and retain the best staff members and students:

- Capabilities of the academic staff (CV’s, involvement in the teaching, research and administrative activities of the evaluated department, etc.);

- Demography of the staff (age distribution, gender balance), existence of performance review, training and succession plan for the staff;

- Existing infrastructure (laboratories, soft/codes, etc.);

- Curriculum;

- Course and application description;

- Average time for the completion of the programme

- Involvement in research programmes or projects related to the chosen technical field (mainly for Masters).

Qualitative and quantitative criteria

The qualitative criteria define the ‘must do’ of the educational programme, while the quantitative components impose a threshold and give the control instrument for quantifying performance. These criteria establish the standard. The standard should be high and challenging to reach.

Peer review

The accrediting organization will nominate a peer review committee or commission to evaluate the performance of the accredited faculty/department. The reviewers should have the competence and standing in the field to serve as an objective reviewer. In addition, the accrediting organization should seek feedback from the faculty/department regarding the reviewers to assure that they are qualified to serve in this role.

After having examined the self-evaluation report, the committee/commission will carry out a visit to the faculty/department for an on-site review. The visit should include interviews with professors, students and administrators, tours of teaching laboratories and facilities, and observations of student output including homework assignments, papers and examinations. Based on all this information, the committee/commission issues its conclusions if the programme has met the standards, criteria and performance indicators.

Faculty/department feedback

The faculty/department should have an opportunity to see the report and respond to issues and recommendations that have been made. These responses should be taken into account by the accrediting organization in arriving at the final conclusions and actions. In most cases, the faculty/department will be given some period of time to implement any needed changes or improvements.

Final accreditation

Upon consideration of the committee/commission report and any response from the university, an accrediting organization will decide to maintain/approve or deny accreditation of the programme. Provisional accreditation may also be granted pending an interim review. Experience has indicated that the accreditation process is time consuming and involves essentially all academic staff of a faculty/department. It shows not only the potential to provide a specific programme, but also the organizational capability. However, the accreditation process with well-defined standards and periodic reviews are critical in assuring the quality and timeliness of academic programmes.

Source: Nuclear engineering education: A competence-based approach in curricula development

References

[1]