Implementation of a Process-based Mgmt System

Contents

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 Implementation Process

- 3 Evaluate business needs and define requirements

- 4 Prepare an IMPLEMENTATION PROPOSAL and Strategy

- 5 Establish the Development Team

- 6 Develop the Process Framework and StanDards

- 7 Develop the Implementation Plan

- 8 Process development and deployment

- 8.1 Identify Process to Develop

- 8.2 Form Process Team

- 8.3 Identify Process Requirements and Scope

- 8.4 Capture Existing Practices

- 8.5 Identify Gaps and Areas for Improvement

- 8.6 Develop Process Activities and Flowchart

- 8.7 Develop Process and Procedural Documents

- 8.8 Implement the Process

- 8.9 Review Effectiveness of Implementation

- 8.10 Continual Improvement

- 9 Summary

- 10 Appendix I

- 11 Elements of Management Systems

- 12 APPENDIX II

- 13 Identifying Processes

- 14 REFERENCES

- 15 Glossary

- 16 Annex I

- 17 Example Outline of a Project Charter

- 18 ==

- 18.1 Process maturity Assessment

- 18.2 Benchmarking organizational change

- 18.3 Annex IV

- 18.4 Risk Management

- 18.5 Annex V

- 18.6 Communication

- 18.7 Annex VI

- 18.8 Examples of Process Models

- 18.9 Annex VII

- 18.10 Example Top level Process Description Template

- 18.11 Annex VIII

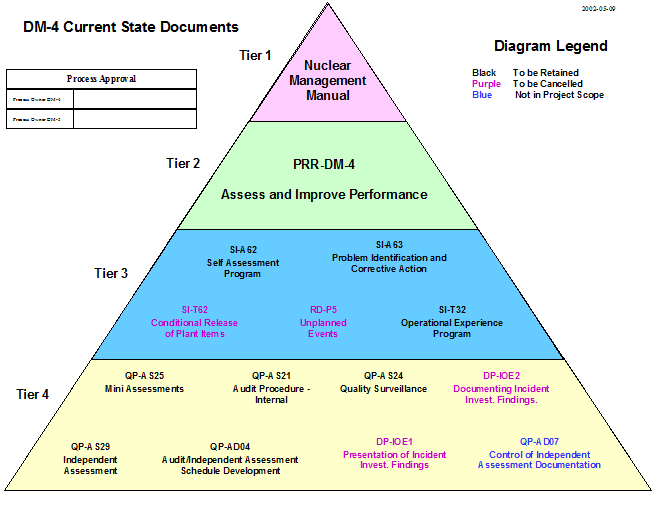

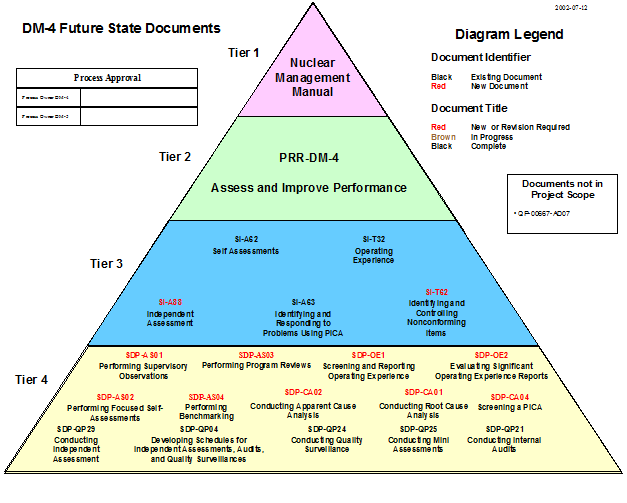

- 18.12 Example Process Document Hierarchy

- 18.13 Annex IX

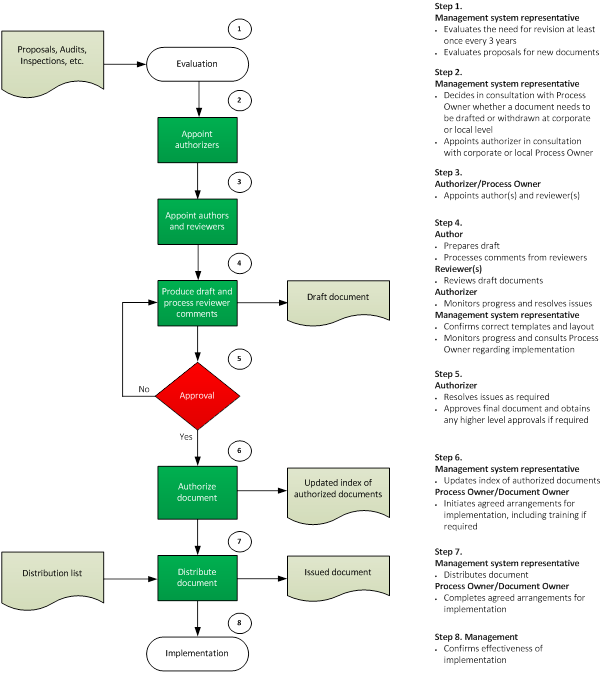

- 18.14 Example of DOCUMENT Administration Process

- 18.15 Annex X

- 18.16 Example of implementation schedule

- 18.17 CONTRIBUTORS TO DRAFTING AND REVIEW

NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES No. NG – T-1.3

IMPLIMENTING A PROCESS BASED MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY

VIENNA, 2013

p.; 24 cm. — (Nuclear Energy Series Guide, ISSN 1080–745x; no. xx)

STI/PUB/167x

ISBN 92–0–111107–x

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Nuclear facilities — Management.

2. MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS management — Standards.

3. Radiation — Safety measures. I. International Atomic Energy Agency.

II. Series: Safety standards series, GS-R-3, GS-G-3.1, GS-G-3.5; Safety reports series, No. 22 (IAEA GS-R-3 vs. ISO 9001:2000), No. xx (IAEA GS-R-3 vs. ISO 9001:2008), No. xy (IAEA GS-R-3 vs. ASME NQA-1-2008)

| IAEAL | 02–0077x |

FOREWORD

One of the IAEA’s statutory objectives is to "seek to accelerate and enlarge the contribution of atomic energy to peace, health and prosperity throughout the world". One way this objective is achieved is through the publication of a range of technical series. Two of these are the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series and the IAEA Safety Standards Series.

According to Article III, A.6, of the IAEA’s Statute, safety standards establish "standards of safety for protection of health and minimization of danger to life and property." The safety standards include the Safety Fundamentals, Safety Requirements, and Safety Guides. These standards are written primarily in a regulatory style, and are binding on the IAEA for its own programmes. The principal users are Member State regulatory bodies and other national authorities.

The IAEA Nuclear Energy Series comprises reports designed to encourage and assist R&D on, and practical application of, nuclear energy for peaceful uses. This includes practical examples to be used by owners and operators of utilities, implementing organizations, academia, and government officials in Member States, among others. This information is presented in guides, reports on technology status and advances, and best practices for peaceful uses of nuclear energy based on inputs from international experts. The IAEA Nuclear Energy Series complements the IAEA Safety Standards Series.

IAEA Safety Standards reflect an international consensus on what constitutes a high level of safety for protecting people and the environment. Safety Requirements are one of the categories of IAEA Safety Standards. They establish the requirements that must be met to ensure the protection of people and the environment, both now and in the future. The requirements, which are expressed as ’shall’ statements, are governed by the objectives, concepts and principles of the Safety Fundamentals. The Safety Requirements use regulatory language to enable them to be incorporated into national laws and regulations. The IAEA Safety Guides give guidance how the requirements can be met.

In addition to the safety requirements and safety guides, the IAEA also produces a wide range of technical publications and reports to help Member States in developing national infrastructure and associated standards. The technical report series provides international best practices in the application of the IAEA Safety Standards series. These publications use permissive rather than regulatory language, as they are intended to provide examples. They are not intended to be incorporated into national laws or regulations. The guidance provided is based on expert judgement: they do not stem from a consensus of IAEA Member States. The guidance provided does not relieve the users of their responsibilities to comply with the requirements of the standards. The IAEA Safety Standards Series No. GS-R-3 defines the requirements for establishing, implementing, assessing and continually improving a management system that integrates safety, health, environmental, security, quality, and economic elements. The safety guides GS-G-3.1 through GS-G-3.5 provide guidance on how the requirements of GS-R-3 can be met for the different installations and activities.

A management system designed to fulfil the requirements of GS-R-3 treats work as a set of processes that meet these integrated requirements. Implementing such a management system requires management commitment and leadership. This publication provides information to help both emerging nuclear organizations and mature organizations wishing to make the transition from a QA/QC based management system to one that meets the latest IAEA requirements and guidance on management systems for nuclear facilities and activities.

The IAEA wishes to thank and acknowledge the efforts and valuable assistance of the contributors to this publication, who are listed at the end of this publication, for their contribution to the development of this publication. The IAEA also wishes to thank the organizations of the contributors for permission to include the practical examples provided in this report. The Scientific Secretaries responsible for the preparation of this publication was J.P. Boogaard of the Division of Nuclear Power.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Background

The IAEA has established, in IAEA Safety Standards Series No. GS-R-3 [1], requirements for establishing, implementing, assessing and continually improving a management system that integrates safety, health, environmental, security, quality, and economic elements. IAEA Safety Standards Series No. GS-G-3.1 [2], GS-G-3.5 [3] and similar IAEA Safety Guides specific to technical areas provide guidance on how to fulfil the requirements specified in IAEA GS-R-3.

GS-R-3 defines requirements for establishing, implementing, assessing and continually improving a management system that integrates safety, health, environmental, security, quality and economic elements to ensure that safety is properly taken into account in all the activities of an organization. Such a management system is often referred to as an integrated management system. The management system approach identified in the IAEA standards and guides also requires increased attention to processes in the context of a functional organization. This can be challenging for many organizations accustomed to traditional, non-integrated, non-process based approaches to management systems.

For Member States with quality assurance/quality control systems, establishing such a process based management system involves a transition from programmes or systems based on quality assurance or quality management standards. Consequently users of IAEA Quality Assurance Code and Guides Q1-Q14 [4], ISO 9001 standard [5], or ASME-NQA-1-2008 and related addenda [6] on quality management often find it challenging to implement the latest IAEA standards on management systems. In addition to the challenges associated with conceptual and scope shifts, organizations may be concerned that the adoption of a management system based on GS-R-3 may result in the loss of certifications or qualifications under specific management system standards. This arises largely from a misunderstanding of the latest IAEA requirements for management systems, and what the transition to a process based management systems and meeting the new requirements actually entails.

A process based management system enhances traditional quality programmes, and when properly implemented, enables the organization to satisfy external agencies/registrars for certification of management systems such as ISO 9001, ISO 14001 [7], OHSAS 18001 [8], and regulatory acceptance of security and safeguards programmes. It also assures knowledge retention and the retention of all important aspects of existing programmes. As part of, and to facilitate implementation, organizations can develop maps, descriptions and other documents demonstrating how the certified quality assurance and quality management programmes are addressed in the process based management system documents such as the latest guidance comparing IAEA GS-R-3 requirements with ISO 9001 [9], or comparing IAEA GS-R-3 requirements with ASME NQA-1 [10] may be used to help create such maps or documents.

A vendor-provided "management system" delivered with a nuclear power plant to ensure safe operation is often a typical quality management system for operations and maintenance, which to a certain extent may integrate aspects related to safety and environmental protection. GS-R-3, however, requires the organization to identify processes of the management system needed to achieve the goals, meet all requirements, and deliver the products of the organization. Furthermore, such processes must be planned, implemented, assessed and continually improved. This means that a management system conforming to GS-R-3 [Ref. 1] must be tailored to meet the objectives and requirements of the organization and specifics of applicable licenses. As a consequence a quality assurance (management) system needs to undergo a transition as indicated earlier.The guidance provided in this publication has to be used in conjunction with IAEA guidance on continual improvement [11] and on Managing Organizational Change In Nuclear Organizations [12]. This publication contains information on how to make the transition from a quality management system to one aligned with IAEA requirements for management systems, thereby providing Member States and organizations wishing to adopt the new standards with guidance that reduces resistance to, and facilitates, such an undertaking. The guidance will enable Member States and organizations to introduce, apply, and meet, the new requirements in a planned and systematic manner, without losing any gains in safety performance or operational efficiency and effectiveness derived from their existing quality management systems.

The publication focuses on the steps an organization can take to implement or make the transition from quality assurance (QA) and quality management (QM) to a management system meeting IAEA GS-R-3 requirements, including:

- Understanding the major differences and similarities between QA/QM systems and management systems;

- Setting policies, goals and objectives and preparing the organization to implement a process based management system;

- Developing strategies and options, and engaging stakeholders;

- Developing detailed plans for implementation;

- Making the transition;

- Assessing the effectiveness of implementation, learning lessons, sustaining the change and continually improving.

Objective

The objective of this Nuclear Energy (NE) Series Report is to provide good practice, practical examples, and methods that can be used to help organizations implement a process based management system as defined by IAEA Safety Standards GS-R-3.

Scope

This publication provides guidance on implementing a process based management system to all life cycle stages of nuclear facilities and activities, including siting, design, construction, commissioning, operation and decommissioning. As such it can be applied to organizations implementing a management system for the first time, as well as to organizations wishing to make the transition from legacy management systems such as those based on quality assurance (QA) and quality management (QM) approaches.

Users

The publication will be of interest to organizations wishing to develop a process based management systems that comply with IAEA requirements and guidance on management systems, either on a voluntary basis, or as a requirement specified by a regulatory body. Thus, this publication is intended for:

- Operators of nuclear facilities and activities who are either legally obliged, or choose as best practice, to implement the requirements of IAEA GS-R-3;

- Suppliers of products or services that are required to be produced in accordance with the requirements of IAEA GS-R-3;

- Regulatory bodies that wish to use this document as guidance for their licensees;

- Regulatory bodies that wish to meet the requirements of IAEA GS-R-3 in their own management systems.

Implementation Process

Implementation of a process based management system is an implementation of change and can be done in various ways, however, experience has demonstrated that the adoption of a structured approach provides the best guarantee of success, efficiency and long term sustainability. Implementation may involve either the creation of a new system (embarking countries or organizations) or transition from a mature QA/QC system into a process based management system. In either case the process to be followed is the same, even in the case of embarking countries where the detailed operating procedures (operation, maintenance, radiation protection, surveillance requirements, etc.) are delivered by the vendor as part of the installation.

The preferred approach is to manage the implementation effort as a project with a project manager and supporting staff (development team) as needed. The size and complexity of the effort to establish a process based management system or to transition an organization from its current-state management system, is proportionate to:

- the identified gap between the current state of the management system and the intended outcome after implementation;

- the type, size, and complexity of the organization.

An organization has to assess its individual situation and, using a graded approach, scale the requirements and activities to manage the development and implementation in accordance with its needs.

The elements to be considered in the graded approach are:

- A senior management decision to implement a process based management system, and allocate required resources for that effort, may be based on a documented implementation proposal (business case) weighing the resources (i.e. costs) versus expected benefits. However, there may be situations in which a decision has been imposed on an organization by a regulatory body, corporate body, client, or stakeholder. This may void the need for preparing an implementation proposal or simplify its content. (See the Glossary for a definition of the term ’implementation proposal’ and other terms used in this section).

- If an implementation proposal is prepared, the typical size of such a document is usually a few pages. The complexity of the content depends on the size of the organization and the decision-making process used by senior management.

- Following approval of the implementation proposal, a project charter authorizing the execution of a project is often formally issued. This is usually the case in an organization that has a structured project management process in place. In an organization that does not have a structured project management process the function of the project charter may be carried out by a memorandum or other communication vehicle, or may be included as an item on the organization’s business plan and assigned to a responsible individual.

- The specific project implementation plan supporting the project charter should be documented. Organizations that already have a defined project management process generally deploy that process and the available project plan templates. The project management process typically scales the plan to the size and complexity of the implementation. If an organization does not have a defined project management process, the project manager should scale the plan to the size and complexity of the implementation in consultancy with the senior manager. Typically, for a smaller project, the project plan will be less elaborate than for a large scope project implemented by a large team, sometimes operating across multiple sites.

Besides a graded approach for the transition project itself, the application of the management system requirements also has to be graded as required by Ref. [1] to ensure appropriate application of resources and controls. The following considerations apply to grading of the application of the management system requirements:

- The significance for safety, health, environmental, security, quality, and economic aspects and complexity of each product, item, system, structure or component, service, activity, or controls;

- The hazards and the magnitude of the potential impact (risks) associated with the safety, health, environmental, security, quality and economic aspects of each product, service, activity, or controls;

- The possible consequences if an item, system, structure or component fails or an activity is carried out incorrectly.

Detailed guidance in grading the application of management system requirements is provided in Ref. [13]. A sample template of a project charter is presented in Annex 1.

The implementation process can be broken down into three main activities:

- Evaluating the business need and preparing the implementation proposal;

- Managing the development and implementation, and

- Implementing the processes.

Fig. 1 shows the implementation process identifying the key inputs, outputs and responsibilities at each stage. The symbols used in the flowchart are presented in the Glossary. The person responsible for an action is printed in bold in the flowcharts used in this document. For each step in the process, responsibilities have been identified.

FIG. 1. Example of an implementation process.

Although Fig. 1 and other flowcharts in this publication are provided for guidance, the actual activities and sequence will depend on the specific circumstances of each organization. Details associated with Fig. 1 are described in the following sections. .

Evaluate business needs and define requirements

Understand Business Needs

Before an organization begins the implementation of a process based management system, it needs to have a full understanding of the mission and objectives of the organization, its current management system status, and a clear vision of what will be accomplished at the end of the implementation.

The implementation of a process based management system requires a strong commitment by senior management and all management levels of the organization. Since management and staff willingness and capacity to implement the system are important, it is a good practice to assess organizational readiness for the proposed changes. For success, the commitment of the majority of the staff should be solicited before the implementation begins. First the organization should consider its current management system status. It is recognized that most organizations that already have a quality management system have also integrated into that system, to a certain extent, aspects related to safety, health, environment, security, quality, and economics. The extent of integration should be identified to make a correct assessment for establishing the implementation scope, resources, timeline, etc. Annex 2 shows a ’Process Maturity Assessment Table’ which may be used to assess the status of an organization’s system, and facilitate the development of an implementation plan.

The implementation of a process based management system creates an opportunity for the improvement of organizational performance and enhancement of safety, health, environmental, security, quality, and economic aspects. The decision to start the implementation of a process based management system can be a result of:

- Organizational improvement initiatives resulting from performance assessments and continual improvement activities illustrated in Fig. 2, that may include:

- Benchmarking – where the organization has identified the opportunity for improving its performance to align with industry best practices. Some guidance on benchmarking is provided in Annex 3;

- Management review – where the organization’s senior management has reviewed the effectiveness of the existing management system and identified a need to change to a process based management system;

- Stakeholders’ feedback – where feedback shows the need to increase the organization’s performance and transparency of its activities.

- A regulatory requirement – resulting from an alignment of national regulations to IAEA GS-R-3 [Ref. 1]. In this case the requirement is viewed as a licensing requirement to be respected by the organization;

- Corporate requirement – in order to align with corporate and legal requirements related to safety, health, environmental, security, quality, economic, and other objectives.

FIG. 2. Identifying and acting on opportunities for improvement.

For organizations with corporate stakeholders, especially those who build or operate nuclear plants with already established systems, it is important that the implementation aligns with the corporate policies and strategic development and implementation plans. The development and implementation plan should include the training of staff with a focus on their role in the change/implementation process, and the application of the new management system to their duties. Corporate offices are a key stakeholder, as they normally determine resource allocation and provide policies that govern the organization. For a new owner/operator it is important to first develop clear corporate policies, objectives, and a strategic development and implementation plan.

Understand the Management System Requirements

To implement an effective process based management system, the organization should have a clear understanding of what requirements it has to meet as an input for the management system processes, procedures and instructions. These requirements from the various stakeholders include safety, health, environment, security, quality, economics, and various other requirements an organization needs to take into account in order to conduct its business. The requirements should be integrated with a prime focus on safety.

The requirements which have to be met are defined by the stakeholders of an organization.

MediaWiki2WordPlus Converter found a non convertable object. Please send example to developer. http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Word2MediaWikiPlus

FormType = 7

Fig. 3 shows stakeholders as the source of requirements, their relationship and integration into the management system. Requirements related to safety, health, environment, security, quality, and economics take priority over other stakeholders’ requirements.

FIG. 3. Sources of requirements for a process based management system.

Fig. 4 presents another illustration of the integration of requirements in a coherent manner with an emphasis on safety. In this illustration, safety considerations are linked to all other considerations to achieve the ultimate goal of nuclear safety.

FIG. 4. Integration of requirements in a coherent manner with the emphasis on safety.

The organization should consider and understand the overall requirements from various external and internal sources. These requirements may be applied in a graded approach. Detailed guidance on the application of a graded approach to meet the requirements is given in Ref. [13].

Understanding management system requirements means not only understanding the language or letter of a requirement, but also how the organization is expected to comply with the requirement. Hence, the organization should consult with relevant regulatory, corporate/organizational and other relevant authorities and stakeholders to seek clarification of the requirements and to determine or clarify expectations for satisfying these requirements.

Once a common understanding of the requirements and compliance criteria or expectations has been established, the organization should establish a common vocabulary or terminology for communicating requirements and compliance expectations internally and externally. A separate document presenting all the requirements in a logical way, including the applicability of the requirements is often beneficial, not only during the development of the process based management system, but also for the staff and for discussions with the regulatory body. If the process based management system is being developed in the framework of an NPP project it is advisable that the requirements relevant for the siting, design, manufacturing, construction, commissioning, operation, and decommissioning of the NPP be sent to the regulatory body for review and approval where required.

Understand the Current Situation

Before an organization can develop an effective strategy for the implementation of a process based management system, it needs to have a realistic understanding of its starting point or current situation. It should also have a firm understanding of the organization’s business and the impact of the new management system on it. Such understanding is acquired only through detailed analysis and broad consultation.

For the effective implementation of a process based management system, stakeholders should have a clear understanding of the requirements the system has to meet and what treating them in an integrated manner with a strong safety focus entails. As the project evolves, this will require the development team to assess, and provide training and orientation as necessary, to align stakeholders’ understanding of the organization and the requirements and compliance expectations.

Develop a Concept of the Desired Operation of the Future Organization

Based on an understanding of the current state and the process based management system requirements and compliance expectations, senior management needs to paint a picture of what the organization might look like and how it will operate under the new management system. Appendix 1 provides some standard elements useful for the development of a management system. There needs to be a clear vision and high-level understanding of what needs to be accomplished to achieve the desired end-state.

Senior management should review the mission, vision, values, goals and policies of the organization as input to the management system. It is also important to consult with both internal and external (including future) stakeholders to identify, clarify and confirm their needs and understanding of the requirements and compliance expectations, and align all parties as necessary.

Once a common understanding of the requirements and compliance criteria or expectations has been established, the organization should establish a common vocabulary or terminology for communicating the requirements and compliance expectations internally and externally. The organization should also set a firm, commonly understood, and agreed upon, foundation for determining the direction and scope of the implementation and any related organizational changes.

Once the current state and desired future state are known, it is possible to analyse existing processes in terms of potential for optimization in order to enhance effectiveness and control. This can be achieved by performing a gap analysis to identify, for example:

- Missing, redundant, overlapping, orphan, or obsolete processes;

- Processes that do not fully comply with requirements;

- Processes that are currently in use but have operational or regulatory compliance risks (i.e. processes that are currently known to be ineffective or inefficient);

- The maturity of existing processes and supporting documentation;

- Differences in working styles of different organizational units or groups;

- The need to develop or improve the process for managing organizational change.

After the gap analysis has been performed and detailed insights are available, the development team can determine what has to be developed or modified. Several approaches can be used. Normally the top level processes and related supporting documents such as input requirements, checklists, and templates for output documents are defined first and a development and implementation plan is defined and executed.

Although some organizations start to develop and implement the second level documents (specific procedures and instructions) when the top level documents are implemented, most organizations develop the second level documents concurrently with the top level process. In this situation the top level process, the related supporting documents, and the related product-specific documents are implemented at the same time. This approach has the advantage that each process can be implemented throughout the organization in a fully completed state.

To ensure that the implementation of the management system will be successful and sustainable, the basic principles of managing organizational change should be applied. The introduction of a management system will not necessarily mean a complete reorganization, but will typically introduce more logical and efficient working practices and result in some changes in responsibilities.

If the implementation also requires a reorganization of departments, all the aspects of managing organizational change should be applied. In this situation the implementation may take longer and have a bigger impact on the organization with greater potential for resistance to the change. In this situation the scope should be expanded to engage or involve experts on organizational issues to help manage the implementation and organizational change. Detailed guidance for this process is provided in Ref. [12]. Implementation of the organizational change should be planned, controlled, communicated, monitored, tracked and recorded. There are at least two key success factors that enable an effective and successful implementation, and sustainable organizational change:

1. The cultivation and maintenance of a strong safety culture throughout the implementation of the change to ensure that safety is not compromised.

2. Flexibility to accommodate reporting relationships that will work within the context of the organization’s culture during and after the implementation.

The development team and senior management need to understand which factors may challenge the successful implementation within their organization and take appropriate measures to avoid or mitigate them. Annex 4 addresses some risk management aspects related to the implementation of process based management systems.

Additional Considerations for Embarking Countries

This section addresses the needs of embarking nuclear nations and especially the licence holders/operators (industry) who are involved in introducing a nuclear power programme to their country or region. To ensure timely development of the nuclear power project, and to ensure safe operation, all the aspects of safety, health, environment, security, quality, and economics have to be integrated in the management system as required by GS-R-3 [Ref. 1]. The integration of all these elements is essential as early as the start of the project from siting, through construction and commissioning, to ensure that all activities will be carried out safely within the national and international requirements. In the case of embarking nuclear nations, as part of establishing a process based management system, some consideration may first have to be given to establishing the overall framework or management system infrastructure in which to incorporate a process based approach. This section addresses some of these additional considerations.

Any organization whose country has decided to embark on a nuclear power programme and has engaged third parties to support this activity has already given consideration to the quality assurance requirements necessary to ensure confidence that the structures, systems and components will perform satisfactorily in service. This can form the basis of an effective process based management system. The perception that implementing a process based management system may be at the expense of good quality assurance is a misunderstanding that should be addressed by the leadership of nuclear organizations, their suppliers, and regulators, as part of the implementation process. The development of a process based management system is an evolution from a quality management system as described earlier, and any investment already made in defining quality requirements is preserved and will benefit the development of a process based management system. A process based management system framework enhances the confidence in achieving all required results by considering and managing aspects such as safety, health, environment, security, economics and safety culture, in addition to quality.

- Language and translation

The language of the embarking nation is in most cases different from the language of the contractor. This can cause misunderstanding and introduce risk and confusion during the life cycle of the project. Although regulatory requirements are typically written in the native language of the embarking nation, many requirements, standards, and codes are in English as is the case when IAEA and WANO assistance is requested.

Translation of the requirements of codes and standards into a language familiar to both the embarking country and the contractor is to be considered for the contract.

It has been shown that all safety, health, environment, security, quality, and economic requirements have to be considered in an integral way to avoid a negative impact on safety. In addition, integration of requirements already incorporated in the design, manufacturing and construction will bring economic benefits and more efficient operation. Furthermore, operational experience has shown that process based management systems have clearly defined responsibilities, accountabilities and interfaces, which foster safety culture and well-defined safe working practices. These aspects will be especially beneficial when both the main contractor and the future owner/operator develop a management system that will clearly define the responsibilities of both organizations and the interfaces between them.

The language of the management system should be in both the native language of the embarking country and English where appropriate and where the law permits. It must be clearly stated which language has preference in the event of inconsistencies.

One of the challenges of using the native language of an embarking nuclear nation is that in some cases the technical vocabulary related to requirements of the nuclear industry is lacking. In such cases English may be preferred. Additional training focussed on the vocabulary used in the foreign language documents may be required to ensure clear understanding by key staff, particularly if the foreign language is used in contracts, tenders, and standards. A good practice is to use the native language of the contracting nation as the binding language of the contract, putting the onus on the tenderer to ensure the requirements are translated and understood.

- Documents (instructions and manuals)

References 2 and 3 provide guidance on documenting management systems. In addition IAEA TECDOC 1058 [14] provides more detailed guidance on good practices related to preparing procedures within the nuclear industry. Although many good practices and examples of well-designed procedures are available through operating experience exchange and benchmarking, a key factor is to ensure that procedures are designed using modern human factors practices, i.e. that the procedure is easy to use and designed in a manner that minimizes the chances of human error. Some organizations use technical writers trained in procedural design to assist and guide technical subject matter experts in the preparation of procedures.

- Cultural aspects

IAEA Safety Series Report 74 [15] provides specific guidance to embarking countries on implementing a strong safety culture starting with the pre-operational phases. In particular, Ref. [15] addresses the importance of the management system in enabling safety culture and discusses various challenges that typically face embarking countries, including:

- Understanding the significance of nuclear safety and safety culture;

- Managing the complexities arising from multicultural and multinational elements;

- Developing leadership competencies for safety;

- Developing management system processes to support the safety culture;

- Promoting learning and feedback;

- Performing cultural assessments and encouraging continuous improvement;

- Strengthening communication and interfaces.

Although management systems require individuals at all levels of the organization to comply with established processes and procedures (a "compliance culture"), experience within the nuclear industry shows that a healthy safety culture does not force blind compliance to rules through rigid hierarchical systems of authority but encourages open communication, a questioning attitude, mutual respect, and high levels of team and interdisciplinary engagement. The increasingly multinational and multicultural nature of the nuclear industry means that all countries are encouraged to develop a common understanding, terminology, and "language" for safety culture.

- Regulations of the contractor country

Requirements may be different in the contractor country compared with the embarking country (e.g. requirements for environmental assessments). In cases where the embarking country has not yet established an equivalent system of requirements, it may have to rely on the requirements of the contractor country, or specify internationally accepted standards in contracts. In such cases it is desirable to translate such requirements into the language of the embarking country or, where this is impractical, to ensure that a sufficient number of staff within the embarking country are fluent in the source language of the requirements.

Prepare an IMPLEMENTATION PROPOSAL and Strategy

Implementing a process based management system requires dedication and deployment of resources (financial, human, time, etc.). Senior management should understand the benefits and the costs of the implementation when making the decision.

Senior management should appoint a project manager or a change agent who can assess the situation, initiate the implementation efforts though preparation of an implementation proposal (or business case), and lead the development. The change agent also manages the implementation and related organizational changes. The change agent should have a broad understanding of the organization’s business and possess skills in managing organizational change.

The implementation proposal should convince senior management of the benefits of a process based management system. These benefits include:

- Supporting a strong safety culture;

- Identification of the organization’s core, management, and support processes, including sequence, interactions, ownership and accountability;

- Addressing any requirements, needs and expectations;

- Improved understanding of the goals, strategies, plans and objectives of the organization and transparency on how the organization does its work;

- Transparency in responsibilities of various organizational departments and interactions between departments;

- Better identification and management of risk;

- Improved standardization in performing work activities;

- Improved ability in monitoring and measuring organizational performance;

- Optimized use of resources and reduced costs;

- Optimized management system documentation in a structure that avoids duplication, overlap and gaps: all supporting documentation can be identified and referenced from a process;

- Enhanced communication between employees, customers and stakeholders;

- Enhanced employee, customer and stakeholder satisfaction;

- Enhanced safety performance through planning, control and supervision.

Inputs

Prior to starting the preparation of the implementation proposal the change agent should assemble the required input information.

The inputs to the implementation proposal are:

- The vision, mission, values, objectives;

- The critical success factors for the organization;

- Relevant laws, regulations, requirements, management system standards, technical codes and standards;

- Expectations of stakeholders and the internal organization;

- General assessment of the current management system (or QA system) status;

- Assessment of available resources (e.g. human, financial, IT infrastructure);

- Assessment of the organization’s competency and knowledge related to the development and implementation of a process based management system.

Preparation of the implementation proposal

The change agent prepares the implementation proposal. The purpose of the implementation proposal is to provide a basis for senior management to make knowledgeable decisions regarding the development and implementation.

The implementation proposal should be described in a concise document (typically a few pages), preceded by an executive summary. The executive summary should include a statement of what senior management is being asked to approve.

The document content should answer in an informed way the key questions senior management may have when making its decision:

- Why is this needed?

- What will the benefits be?

- What will the cost be?

- What risks to safety and organizational operations might the implementation reduce or cause?

To prepare the implementation proposal the change agent should consider the following:

- the overall development and implementation strategy;

- the scope and realistic timeline of the implementation;

- a brief outline of what the implemented process based management system will look like, and a comparison to the current state;

- the overall benefits to the organization;

- a preliminary estimate of overall costs and resources needed;

- the identification of potential risks to safety and organizational functioning from failure to implement a process based management system;

- the identification of potential unintended risks to safety and organizational functioning resulting from implementation.

Management Approval and Endorsement

When senior management approves the implementation proposal, it should appoint a sponsor, normally a member of the senior management team, who is responsible for overseeing and advising the project manager and resolving issues which lie beyond the responsibilities of the project manager. The project manager is responsible for planning and coordinating the development and implementation efforts. It is recommended that all development and implementation activities be managed as a project.

Senior management should communicate to the entire organization the need for the implementation in order to obtain everybody’s support and commitment. Consistent messages and actions from senior management will have a positive impact on the implementation. When the implementation is in its early stages, communication should focus on "what" and "why" and not on "how". The best form of communication is face-to-face allowing for questions and concerns to be raised and discussed. For larger organizations the face to face communication can be done by the project sponsor and/or project manager, but only after the initial announcement by senior management.

The implementation of a process based management system should be part of the organization’s overall business plan. This will ensure that resources will be provided to support its implementation and also demonstrate that the implementation is a high priority for the organization.

The implementation will introduce a change to the organization. The following are the key conditions for effectively managing the change, in accordance with IAEA Ref. [12]:

- A clear understanding of why the change is necessary;

- A vision of what the organization should look like after the change, and a direction towards that vision;

- Clarity of the end state (the desired outcome);

- Effective management of the implementation (project implementation);

- Effective use of technology;

- Good communication delivering coherent and transparent information that encourages the involvement of people (see Annex 5).

The role of senior management in the implementation is critical. Full support and visible participation of senior management will positively impact the success of the project and the ability to achieve its goals. It is vital that management at all levels support the vision and engage in the necessary activities to improve the existing management system.

Establish the Development Team

Define Composition and Competencies for the Development Team

The appointed project manager should establish the development team as early as possible. The following roles are normally considered as a minimum. Fig. 5 gives an example of a project organization structure.

- Management System Owner: Designated by senior management as the overall "architect" of the management system, this individual coordinates the development of the top level processes, provides standards for top level process development (e.g. templates for flow diagrams and process descriptions), and monitors the interfaces between top level processes during development to ensure proper integration. Provides overall coordination of the development and implementation of the documentation to support the top level processes. Liaises with the designated process owners<ref>For definition of process owner see glossary</ref>.

- Management system specialist (or QA/QC specialist) Provides expert knowledge on management systems standards and QA/QC standards.

- Departmental Representative: Represents a department on behalf of the department head, and provides knowledge regarding the activities in a department. Coordinates the development activities within a department.

- Standards Specialist: Provides expert knowledge of the standards, regulations, codes, requirements, etc. for all process and procedural documents. Together with the project manager, consults the relevant regulatory, corporate/organizational and other relevant authorities and stakeholders to seek clarification of the requirements and determine or clarify their expectations for satisfying the requirements. These expectations should form the criteria for assessing the management system to judge whether or not it meets the requirements. Standard Specialists can also be involved in the review of the documented processes to ensure the requirements are met, and can prepare matrices providing a documented record of compliance against requirements.

- Process Development Specialist: Develops processes in accordance with guidelines established for management system documents. Supports the Process Owner and process-specific development teams in developing processes.

- Steering committee: Provides oversight to the project, including progress monitoring and issue resolution.

- Communications Specialist: Develops, implements, and reviews communication throughout the development and implementation. This individual should be appointed in the early stages of the project to facilitate understanding and engagement of stakeholders.

It must be noted that some functions can be combined. Especially when the management system specialist has good project management skills, this person is then often appointed as project manager.

FIG. 5. Example project structure.

Depending on the specific process, support from individuals in the following areas is generally required: nuclear safety, operations, maintenance, environment, health and safety (including radiation protection), physical security, finance, information technology, human resources, and change management, etc. These individuals may be the (future) process owners for the related processes.

The need for external resources should be considered during the initial development phase of the management system; however, the focus should be on rapid knowledge transfer to enable in-house development and sustainability. Consultants are unlikely to provide an off-the-shelf solution and cannot implement sustainable change without in-house ownership and support.

Assemble and Prepare the Team

The appointed project manager should consult with stakeholders to identify appropriate individuals for the development team based on their understanding of the organization’s structure, activities, requirements, compliance expectations, and the impact of the management system on safety.

If a Standards Specialist is available, this specialist will be involved in consulting stakeholders with respect to the requirements. Requirements include legal obligations, requirements that management (corporate and local) has chosen to adopt based on organizational policies and standards adopted for business reasons or contractual obligations. The requirements will include safety, health, environmental, security, quality, economic, organizational governance, and various other requirements an organization needs to take into account as part of the conduct of its activities, such as:

- National and local legal and regulatory requirements regarding (nuclear) safety, radiation protection, occupational health, environment, security, quality, and emergency preparedness;

- Requirements from the IAEA, including nuclear safety, radiation protection, security, waste management, management systems, training and emergency preparedness;

- Requirements based on guidance from industry organizations such as the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) and the Institute of Nuclear Power Operators (INPO);

- Requirements based on guidance from financial and accounting standards bodies, voluntary private sector organizations, and committees like the Basel Committee, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), or the Criteria of Control Board (COCO) that provide guidance to management on governance, business ethics, internal control, enterprise risk management, fraud, and financial reporting;

- Standards set by national or international organizations, e.g. ISO, the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the National Quality Institute (NQI).

Understanding the requirements means not only understanding the language or letter of the requirement, but also how the organization is expected to comply with or meet the requirement.

Training and orientation should be provided as required to ensure the development team understands the organization, requirements, and compliance expectations, and to develop a process based management system.

Once the development team is assembled and prepared, it can assist with preparing the ’Implementation Plan’; defining the current state and future state of the management system and related organization structure.

Develop the Process Framework and StanDards

Identify Top Level Processes

The senior management team, with the support of the development team, should identify the top level processes that are needed to achieve the goals, provide the means to meet all requirements, and deliver the products of the organization under the new set of management system requirements. This involves identifying the:

- Core processes: the output of which is critical to the success of the facility or activity;

- Management/Executive processes: ensure the operation of the entire management system;

- Support processes (e.g. procurement, training): provide the infrastructure necessary for all other processes.

Appendix 2 provides more detailed guidance on how to identify core, supporting and management processes. It also provides examples of typical core, supporting, and management processes in different nuclear facilities during their entire lifespan. See also Ref. [2, 3].

Develop a Top Level Process Model

The senior management and development team have to consult with the various stakeholders inside and outside the organization to develop a top level process model or framework depicting what the organization and its operations would look like under the new set of management system requirements. Senior management engagement and involvement is essential to securing their on-going ownership of the top level process model. Annex 6 provides several examples of a top level process model, and Annex 7 provides an example of a template for a top level process description.

The establishment of a top-level process model is a critical step for successful integration and implementation. It signals concrete commitment by senior management and the organization to the adoption of a process based approach. Senior management is responsible for determining the extent to which the process approach, and all it entails, will be applied in an organization. Regardless of the degree to which the process approach is adopted and used, it should always be clear who is ultimately responsible for safety and for the performance of the organization as a whole. The measures or indicators that senior management has determined or agreed to be used to judge performance under the process based approach should be clearly communicated and understood by all staff in relation to their duties. Senior management is also responsible for:

- Deciding and assigning authority and responsibility (i.e. accountability – e.g. through the use of process owners) for the functioning or performance of the processes;

- Deciding how power and control, including control of budgets, will be shared, if at all, between process owners and functional managers;

- Establishing the conflict resolution mechanism to be used when the process approach is implemented.

During the initial stages of process development, the organization should focus on the processes, their inputs, activities, and outputs, and not on who is involved in the process.

Establish Accountability and Responsibility

There should be clearly defined roles and responsibilities during and after the implementation. Functional managers should be kept involved and engaged at all times. Effort should be made to show functional managers how process owners can help them. Functional managers should understand the implementation project and its desired end-state to ensure a positive working relationship with process owners. Functional managers may also be considered as potential process owners although delegation of this role to someone actively involved in the day-to-day functioning of the process may be desirable to enable the functional manager to maintain an oversight role. There should be a well-defined conflict resolution mechanism, with senior management retaining full responsibility for the effectiveness of the implementation of the management system, and for safety.

Identify Process Owners

Once the processes are defined, process owners for top level processes can be identified. Process Owner responsibilities are outlined in GS-G-3.5 [3]. Depending on the process, the Process Owner may be a full-time position within the organization or a process role. If it is a process role, it is important that adequate time and resources be made available to effectively fulfil this role. Process ownership should be assigned to the appropriate level of the organization to allow for the effective implementation of processes. When selecting individuals to perform the Process Owner function/role, the following should be considered:

- An ability to understand the need for the process, the process activities, and the process requirements.

- An understanding of where the process fits in the organization, its interfacing processes, and stakeholder needs, i.e. the individual should be a systemic and systematic thinker.

- The motivation to continually monitor the effectiveness and efficiency of the process and to make changes within the authority provided by the senior manager and defined in the management system, when performance degrades or when opportunities to improve performance are identified. The person should take a proactive approach to improvement, rather than wait until the results of audits or assessments indicate deviations.

- The ability to maintain current process documentation.

- The ability to work effectively in a team environment.

- Good managerial and communications skills.

- The ability to monitor industry best practices and make changes to processes to take advantage of the lessons learned.

Establish Process Development Standards and Templates

Establish the Process Framework and Document Hierarchy

Typically the management system is described in a series of documents structured in a hierarchical pyramid. IAEA safety guides (e.g. GS-G-3.1 [2] and GS-G-3.5 [3]) on the implementation of requirements specified in IAEA GS-R-3 [1] describe an example of such a document hierarchy consisting of a three-level structure of information.

The number of levels in the hierarchical structure is established by the organization. There is no one way of depicting the document structure, and each organization should define one that is appropriate to its context. Many organizations have structured their documentation using three or four levels.

The organization needs to identify clearly those documents that describe or implement the management system and those that are outputs of the processes. Each type of document should be assigned to an appropriate level of the hierarchical structure. The following provides information on a typical structure.

Level 1, the top of the pyramid, is the highest level document(s) presenting an overview of how the organization and its management system are designed to meet its policies and objectives. Often these are included in the so called management system manual and contain:

- The mission, vision, goals, policy and the main governing requirements of the management system;

- A brief description of the management system model and its key processes;

- The hierarchical structure of the organization’s documents, which are often detailed in documents associated with the organization’s document control process;

- A high level organizational structure with a brief description of key responsibilities and authorities of senior managers, organizational units, and key committees as applicable;

- Responsibilities of process owners;

- Arrangements for measuring and assessing the effectiveness of the management system.

Level 2 documents consist of the processes to be implemented to achieve the policies and objectives and the designated Process Owner, position, or organizational unit responsible, to carry them out. Level 2 documents consist of:

- Process maps, and processes including the interfaces between related processes;

- Responsibilities, authorities, interface arrangements, measurable objectives, and activities to be carried out.

The information at Level 2 provides administrative direction to managers in all positions and describes the actions that managers have to take or implement. The Level 2 documents may also briefly describe how technical tasks are to be performed.

Level 3 documents consist of detailed procedures, instructions and guidance that enable the processes to be carried out and specification of the position or unit that is to perform the work, including:

- Documents that prescribe the specific details for the performance of tasks by individuals or by small functional groups or teams. The type and format of documents at this level may vary considerably, depending on the application. The primary consideration should be to ensure that the documents are suitable for use by the appropriate individuals and that the contents are clear, concise, unambiguous, and produced in accordance with a template or structure suitable for that type of document.

- Procedures and work instructions defining the steps for performing work activities to achieve a specific analytical, functional, or operational objective: for example, maintenance procedures, operating produces, laboratory procedures, but also procedures for safety analyses, core management, reporting non-conformances, etc.

- Documents that contain data or information, e.g. design documentation and drawings, information reports, etc.

- Job or position descriptions that define the different competencies or types of work encompassing the total scope of an individual’s job. Job descriptions should be used to establish baselines for identifying training and competence needs.

If a 4th level is defined, it typically consists of records and reports providing evidence of the activities which have been carried out. Otherwise these documents also belong to level 3.

Fig. 6 illustrates a 3 level documentation system. This pyramidal structure should be applied to documentation associated with each process, as this will create a consistent structure for the documents and enable quick identification of the position of a document within the hierarchy and the assigned process. The document hierarchy may evolve with the progress of the implementation of the management system; however, carefully thinking through the initial design to include all document types will minimize subsequent change. In some cases, documents may be shared by more than one process. For example, the top level ’Perform Planning process’ and ’Perform Maintenance process’ may share a single supporting document for the planning and implementation of ’Control of Foreign Material. This practice should be considered when referencing one "shared" document, which avoids duplication and ensures consistent understanding and application by the end-user in support of multiple processes.

Fig. 7 provides an example of a regulatory document hierarchy which illustrates the relationship between regulatory framework documents and the internal processes of the regulatory body.

MediaWiki2WordPlus Converter found a non convertable object. Please send example to developer. http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Word2MediaWikiPlus

FormType = 7

FIG. 6. An example hierarchy of documents in a process based management system''.

FIG. 7. Example hierarchy of documents for a regulatory body.

Annex 8 provides examples of a hierarchy of documents associated with one of the processes in a process model, before and after the implementation.

Establish Document Templates

The development team, in consultation with the relevant stakeholders within the organization, should establish templates, or documentation standards, for describing processes, procedures, forms, and other routinely produced documents in the management system. These templates should be used by the organization to facilitate development of documents. Consistency ensures a uniform style, reduces error at the time of use, and facilitates inter-departmental training.

The templates for the different types of documents describing the management system (process descriptions, working level procedures, etc.) should be described in the document control process procedures in order to ensure that a standard format is used for each category of document. The responsibility for developing the different templates should be defined in the top level process. The templates for the corporate processes and the control mechanism for all documents should be defined at the corporate level to ensure a standard to control all documents, since different activities may require different templates.

Each document requires a unique identifier. It is advisable to define a document identification system related to the document structure and level of the documents in the management system. Some organizations indicate the process and level of the document in the cover sheet. Fig. 8 shows a 4 level structure. The shading on the diagram indicates that the specific document is at Level 3.

FIG. 8. Identifying the level of a document in the hierarchy.

The number of documents should be optimized to permit easier control of the system. Documents should be designed with the end user in mind in order to aid effective implementation at the time of performance. The use of flowcharts in the documentation is encouraged. When using flowcharts, flowcharting standards (e.g. INPO or examples provided in this publication) should be identified and used to support a uniform application and understanding.

Establish a Methodology for Developing Processes

In order to ensure consistency in the description of processes, a specific process describing the preparation, review and approval of management system documents should be established. This process should clearly describe the responsibility for the development of documents of each type and level. An example of the administration of management system documents is presented in Annex 9. The owner of this process could be the Process Owner of the document control process or alternatively this role could be assigned to the Management System Owner.

Develop the Implementation Plan

Implementation Plan

An implementation plan should be prepared by the development team to describe the activities required for successful implementation. The implementation plan should align with the project charter and the implementation strategy. The implementation plan governs only project activities and therefore should reference and direct the user to the use of existing processes such as document control and project management. If those processes are not yet available they should be developed as early activities in the Implementation Plan.

The implementation plan normally includes:

- Purpose and scope of the implementation (from the project charter and implementation strategy);

- An implementation project organizational chart;

- Structure, tasks and responsibilities and authorities of the project team members, steering committee, specialists, and other key positions;

- Tasks and responsibilities of the organizational divisions, departments, units, groups, and other specialists/staff involved in the development and implementation;

- Planning, including schedule, timelines and milestones (an example of a schedule with milestones is given in Annex 10);

- A detailed breakdown of the project resource requirements, including project team resources, external resources if required, and anticipated management and department resources required to support oversight, development and initial implementation;

- Identification and prioritization of the risks associated with the project (e.g. implementation delays, resource constraints, implementation issues) and a risk reporting strategy. Include the future impact of the implementation or change by considering the:

- Safety impact of the proposed change, additional measures might be necessary to ensure that the change does not have a negative impact on safety;

- Change readiness and commitment of the organization;

- Impact on organizational culture and behavior;

- Impact on organizational responsibilities and structure;

- Impact on performance effectiveness;

- Potential impacts on organizational planning, performance monitoring and performance indicators;

- Impact on stakeholders and interfaces (both internal and external).

- Training requirements (e.g. process owners, internal auditors and other stakeholders);

- Implementation activities including:

- Schedule, timelines and milestone controls;

- Preparation of the process development and implementation plans for each specific process, including priority, sequence of development, and disposition of the issues identified during the gap analysis;

- Project reporting (milestones, progress and budget);

- Process implementation, roll-out and/or training;

- Implementation monitoring and oversight including:

- Oversight meetings, lessons learned, and issue resolution;

- Evaluation of implementation effectiveness through stakeholder feedback, self-assessments, audits, management review, etc.

- Project close-out.

- Architecture for supporting documentation; including:

- Development of the Level 1 management system document, as required;

- Management system development standards (e.g. process design, flowcharting and documentation standards and/or templates, software to be used, etc.).

- Organizational Project Management methodologies;

- Communication plan;

- Change management methodology appropriate for the type and scope of the change. If change management expertise is required but not available within the development team, it should be obtained either internally (from within the organization or by training a member of the development team) or externally. Reference 12 gives detailed guidance on managing change in nuclear organizations, and much additional literature is available, as for example Ref. [16, 17];

- Significance of the identified gaps and a strategy to address the gaps.

As processes are frequently dependent on input from each other there may be a need to develop certain processes before others. This is particularly important when developing processes for a new organization. For example, processes to ensure consistent development and management of process and procedural documents are an early requisite, as are processes most in need of improvement to support on-going work. Prioritization should take into account the organizational needs and stakeholder requirements. However as processes are developed, individual interactions and changes in the internal and external environments may require processes to be developed in parallel or in a different order.

The definition of the management system framework, structure and document format should be given priority as it enables consistent development and description of processes. The process for preparation, review and approval of management system documentation should be the first ones to be developed and approved. Annex 9 provides an example of such a process. To ensure consistency it is important to appoint a person with overall responsibility for the management system.

A Communications Specialist should be involved in preparing a communications plan that considers stakeholders directly involved in the accomplishment of the organization’s mission and goals, establishes lines of communication, and consults with stakeholders in decision-making which may affect them. This can be achieved only through open communication and understanding the stakeholders. Consideration should be given to whether some stakeholders who are indirectly involved in the accomplishment of the mission and goals should be involved in the preparation and implementation of the communication plan.

The implementation plan has to be submitted to senior management for final approval. Once the implementation plan has been approved, the project charter may require revision to update key areas such as resources, milestones, timelines, budget, etc. Revisions to the project charter typically require approval of the steering committee.

Implementation and Progress Reporting

Throughout the implementation, the development team and senior management should monitor and collect feedback on the progress of the implementation and take concrete, visible actions based on this feedback.

The following methods are normally used to monitor and obtain feedback on the implementation:

- Internal audits;

- External audits;

- Self-assessments;

- Improvement proposals;

- Non-conformance reporting;

- Management reviews.

Reference 2 gives specific guidance related to measurement, monitoring and improvement processes.

The implementation plan should be revised if required and the new revision should be approved at the appropriate level.

On a regular basis, progress reports should be prepared by the project manager and submitted to the project sponsor, steering committee and senior management. The following aspects are normally included in a progress report:

- A summary of the process development, roll-out/training and effectiveness review process;

- Summary of human and financial resources used;

- Progress in relation to project milestones;

- Challenges, potential solutions and the issue resolution process to be used;

- Updates on the risk identification and mitigation process.

If there is a change in scope, budget, resources, or timeline, the implementation plan should be changed accordingly, and approved at the appropriate level.

In addition to the implementation plan, terms of reference (authorities, responsibilities, membership, frequency of meeting, etc.) should be developed for the steering committee and for the development team. The terms of reference may be included in the implementation plan.

Communicate the Implementation Plan

Communication to foster understanding, engage stakeholders, and solicit feedback should begin at the conceptual stage of the project and continue at every stage to ensure there are no surprises for participants or stakeholders. Once the implementation plan has been approved, communicate the plan to internal and external stakeholders as appropriate.

To foster acceptance for the plan and its implementation, including organizational change, the strategy and plan should be packaged and communicated to all levels of the organization as a positive undertaking that highlights the tangible benefits for all management and staff.

The development team, other project teams and all levels of management should use appropriate communication channels or modalities available to them to periodically inform the organization and its stakeholders about the implementation of the management system, including the progress being made and any significant issues. The communication channels should focus on face-to-face interactions, supported by leaflets, memos, e-mail and the intranet. Frequently asked questions and answers should be posted on the organization’s intranet.

The organization may use individuals who will promote the implementation within their organizational units (i.e. change agents). These individuals, the development team and senior management should be aided by the Communications Specialist and the developed communication tools to deliver effective messages to the organization and its stakeholders.

Management Commitment

Management at all levels has to demonstrate active commitment to the establishment, implementation, assessment and continual improvement of the management system and shall allocate adequate resources to carry out these activities. For the success of the project this commitment must not only be a written statement but must be visibly shown in all actions and decisions.

If not yet developed, senior management should develop individual values, institutional values and behavioural expectations for the organization to support the implementation of the management system and must act as role models in the promulgation of these values and expectations.

These individual values, institutional values and behavioural expectations must be clearly communicated to the staff. Senior management should explain the importance of adopting the values, and the expectation that the processes, procedures and instructions of the management system be followed. They should also stress that proposals for improvement should be communicated to management and the development team in order to improve the management system.

Management at all levels should foster the involvement of all individuals in the implementation and continual improvement of the management system.

Process development and deployment

Previous sections have indicated that a top level model or framework typically identifies the main processes for the organization. Each process requires the development of individual sub-processes or procedures to support each main process and its subsequent implementation across the organization. The objective is to apply a consistent methodology to develop processes that meet all external requirements, standards and organizational objectives while minimizing duplication. The development will be influenced by the maturity of the organization and the availability, quality, and complexity of existing procedures.

The Process Owner is responsible for coordinating the development and implementation of the process with support from the development team as needed. Depending on the complexity, development may make use of a support team and specific plans to manage the development and implementation of the process.

Identifying and understanding the requirements in terms of inputs, outputs, and constraints is a key element for producing an effective process.

The steps for development of a specific process are shown in Fig. 9, and each step is described in Sections 8.1 through 8.10.

FIG. 9. Process Development and Implementation.

Identify Process to Develop