Community of practice

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Summary

- 3 Description 1

- 4 Description 2

- 4.1 CoP background and history;

- 4.2 Description

- 4.3 General criteria for assessing the business maturity of CoPs;

- 4.4 Community of practice approach

- 4.5 Factors leading to formation of CoPs

- 4.6 Industry process ownership

- 4.7 Sustaining factors

- 4.8 Integration of process knowledge and collection of best practices

- 4.9 Role of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems

- 4.10 Role of third party software solutions

- 4.11 Custom solutions

- 4.12 Termination of active industry programme

- 4.13 CoP and SIGs

- 4.14 CoP list

- 4.14.1 Configuration management benchmarking group

- 4.14.2 Equipment reliability working group

- 4.14.3 Nuclear supply chain strategic leadership (NSCSL, CoP)

- 4.14.4 Nuclear information technology strategic leadership (CoP)

- 4.14.5 Nuclear asset management CoP

- 4.14.6 Nuclear information management strategic leadership (CoP)

- 4.14.7 Nuclear human resources group (CoP)

- 4.14.8 Licensing community (CoP)

- 4.14.9 Fire protection (CoP)

- 4.14.10 Work Management Working Group

- 4.15 CoP benchmarking methods

- 5 References

- 6 Related articles

Definition

Community of practice is/are A voluntary group of peer practitioners who share lessons learned methods and best practices in a given discipline or for specialized work. The term also refers to a networks of people who work on similar processes or in similar disciplines, and who come together to develop and share their knowledge in that field for the benefit of both themselves and their organization(s).

Source: Comparative Analysis of Methods and Tools for Nuclear Knowledge Preservation

Source: Process oriented knowledge management

Community of practice is Template:Community of practice 2

Source: Planning and Execution of Knowledge Management Assist Missions for Nuclear Organizations

Summary

One paragaph summary which summarises the main ideas of the article.

Description 1

Community of practice (CoP) is a network of people who work on similar processes or in similar disciplines, and who come together to develop and share their knowledge in that field for the benefit of both themselves and their organization. The original thoughts behind the concept of a CoP are generally attributed to E. Wenger, and the techniques and benefits are described in his book [8]. CoPs are generally self-organizing and usually emerge naturally but need management commitment to get started and continue working effectively. They typically exist from the recognition of a specific need or problem and are particularly important in realising benefits in R&D organizations through increased innovation and collaboration. A CoP provides an environment (face-to-face and/or virtual) to connect people and encourage the sharing of new ideas, developments and strategies. This environment encourages faster problem solving, cuts down on duplication of effort, and provides potentially unlimited access to expertise inside and outside the organization. Information technology now allows people to network, share and develop ideas entirely online. Virtual communities can thus help R&D organizations overcome the challenges of geographical boundaries.

Source:

Knowledge Management for Nuclear Research and Development Organizations

Description 2

CoP background and history;

In this Appendix the development and methods of US communities of practice (CoP) are presented covering a period of time of about 1999–2008 (see Ref. [22]). NEI originally conceived the concept of communities of practice as part of a global trend in CoPs beginning about 1999. NEI’s definition of a CoP is: An effective new organizational form, called a community of practice, has emerged that promises to capitalize on existing industry structures and expand opportunities for knowledge sharing, learning, and change management. Communities of practice are groups of people who come together to share and to learn from one another face-to-face and virtually. They are bound together by shared expertise and passion in a body of knowledge and are driven by a desire and need to share problems, experience, insights, templates, tools and best practices.

Description

A community of practice as an industry peer group of experts in a business process or sub-process defined in the SNPM. The group serves as the ‘owner’ of a particular process or sub-process, managing the solution of issues for the industry in that area. A sample of responsibilities performed or supported by a CoP is listed below: — Develop, approve and adjust process Key Performance Indicators; — Recommend adjustments to cost definitions in the SNPM; — Support and guide industry management of strategic business process issues; — Agree on and administer appropriate industry projects for their process area; — Integrate, coordinate and provide guidance to special issue group activities to gain synergies on related industry process issues; — Determine future benchmarking needs.

General criteria for assessing the business maturity of CoPs;

A typical community of practice has taken about six months to become chartered and operational and at about the one-year-point the organization is normally capable of developing and implementing improvement projects. Assessment of full capabilities can be determined based on the following attributes, capabilities and work products: — The formation of a leadership or steering team; — An agreed upon Community of Practice charter describing process scope, how the team will work together and their focus areas; — Publication of a documented process description, typically in ‘AP-XXX’ format containing: • Process generic steps and logic maintained in at least three hierarchical levels; • A set of definitions of industry-wide performance indicators; • A set of fully developed process cost definitions for each sub-process; — Management of a set of performance improvement projects that are coordinated with interfacing CoPs through the NAM CoP as required; — Ability to assist in the process orientation of new CoP members; — When applicable, coordinate and align the activities of related special issue groups. Achievement of all the above items has typically taken about three years. A table of CoP characteristics is summarized in Table 4.

Community of practice approach

The details concerning how CoPs appeared are best explained as part of the ‘Benchmarking loop’ discussed in article "Benchmarking"

Factors leading to formation of CoPs

Several factors are considered when considering the formation of a CoP. Foremost is the goal of identifying the most effective collection of industry professionals who can manage the business aspects of the process. They must be subject matter experts and they must be will to accept some responsibility for creating and maintaining their body of knowledge. They must also be willing to work within the system described by the SNPM to facilitate their enabling processes or process interfaces to optimize the overall business of nuclear electricity generation. Industry sponsorship is also an important factor to convince potential members of the benefits of CoPs. All CoPs were formed in one of the following ways: — An existing SIG became the CoP as a result of exposure to the benchmarking programme; — CoP was similarly formed by the adding together of one or more SIGs; — CoP was formed by like-minded subject matter experts as a result of attending a benchmarking workshop.

Industry process ownership

About 1994, INPO began a project to develop improved process descriptions for the ‘Advanced plant’ (AP). A series of the AP documents were drafted by INPO staff and reviewed by industry peer subject matter experts. These documents were envisioned to become part of a utility’s ‘Advanced Light Water Reactor (ALWR) Toolkit’. Since new nuclear plants ‘had not yet arrived’, the project was closed in 1997, but efforts continued to further develop some APs based on demand from INPO members companies. The best example of this is AP-928, INPO Work Management Process Description. Some utilities embraced the idea of improved industry process and used the AP documents series as a template starting point. Therefore some immediate benefits were achieved about 1995–1998 as this was also the time when formal NEI benchmarking projects began to provide Best Practices for consideration. Upon issuance of the SNPM Rev.0 in 1998, the concept of industry process ownership resided with INPO. However several of the ‘dormant’ APs described processes that were not part of INPO’s normal plant evaluation or assistance processes. This effectively had taken the processes ‘off the radar screen’. After taking the economic points of contact benchmarking poll in 1999, NEI worked with INPO to ‘transfer’ the following APs to NEI in 2001: — AP-902 – waste services; — AP-907 – processes and procedures; — AP-908 – materials and services. NEI was also assumed to be the industry process sponsor for all support services processes such as: — Information technology; — Business services; — Human resources; — All loss prevention processes (LP002 shared with INPO); — Nuclear fuel process. NEI began the practice of labelling industry process ownership in the SNPM, Rev.1. Ongoing involvement by CoPs offered several advantages not seen in other industries: — Knowledge management captured within: • Process description; • Key performance measures; — Integration of process steps by consensus with interfacing CoPs; and — Completion of high-value projects for the industry.

Sustaining factors

CoPs become expert managers of knowledge if, after formation, they can establish some sustaining activities that demonstrate value to the industry. There are several factors that tend to sustain these groups over time. These include: — Executive sponsorship; — Industry-level sponsorship (NEI, INPO, EPRI); — Availability of 5–7 members who are willing to be CoP leaders; — Recognized products and services; — Mentorship role for new members; — Creating value based on number of meetings and location, cost of meetings; — Achieving a balance between improvement projects established and the number of members available who are able to work on those projects, such that the total amount of work required is available from the members.

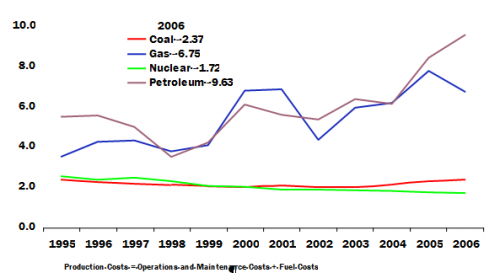

Integration of process knowledge and collection of best practices

As a result of deregulation, the benchmarking programmes and other safety and efficiency drivers, all utilities began to seek and implement best practices wherever possible beginning about 1992. Because of the large number of utility peer visits, INPO evaluations, NRC inspections and consulting engagements conducted, it is difficult to say exactly when, where and how many of these best practices occurred. However these forces were certainly aided by the INPO sharing principle and the NEI benchmarking programme. This can be seen by the overall reduction of O&M costs in progressive fashion beginning about 1997 and continuing until present day (see Fig. 23).

Role of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems

Commercial computer software for managing maintenance work and integrating the supply chain began to appear about 1990. Many utilities also internally developed corporate versions for accomplishing this work or deployed a series of software programs with assigned functions. Over the next ten years best practices were captured and integrated into several large product offerings that became a ‘standard’ for some US fleets. While the larger software products offered more capabilities, there were several potential drawbacks to trusting so much of the business to a single tool such as: — Higher product cost; — Cost and success in implementing the new software and managing the change with employees; — Cost to customize the software for company-specific purposes; — Challenge of integrating other software tools into the overall portfolio. These issues in part gave rise to the NITSL sponsorship of the Computer Software Applications Benchmarking Project in 2003.

Role of third party software solutions

When a new software capability is created, it usually is introduced as a ‘Third party’ (not ERP product and not an existing utility product). Good examples of this are programs that offer capability for monitoring or analysing equipment performance as part of the new equipment reliability process. As these programs become accepted they should be integrated with the ERP software platform or become part of the ERP platform in a new ‘release’. The ability to integrate third party solutions is an important capability for the utility in order to drive improvement as well as to maintain flexibility in overall operations.

Custom solutions

Custom software solutions began to disappear at an increased rate about 2000, as ERP solutions became more robust and as mergers and plant acquisitions allowed nuclear fleets to expand in size. Larger fleets deploying standard processes were more cost effective to manage. By 2006, most fleets operated with one of four ‘standard’ ERP systems. By 2010 most, if not all customized solutions should be a thing of the past.

Termination of active industry programme

About 2004, industry executives were forced to reconsider industry priorities as several important issues began to demand a greater share of ‘issue management budgets’. Some of these issues included higher increased regulatory attention for security, development of materials degradation strategies and improving nuclear fuel reliability. As a result NEI ‘Declared Victory’ for the benchmarking programme and empowered further follow-up to be passed on to CoPs.

CoP and SIGs

In 2005, the industry conducted a thorough review of the function and value of all SIGs (including CoPs). This initiative was led by a working group of Chief Nuclear Officers with dedicated support from NEI, INPO and EPRI as required. Overall categories were established for the review and these were referred to as ‘topical areas’. The industry manager assigned to manage the review of each category was referred to as the Topical area leader (TAL). NEI 05–08 documents project results [25]. As a consequence of the TAL review, many SIGs were disbanded. Others were combined within TAL areas and several were transferred to new industry sponsorship from NEI to EPRI or INPO to EPRI, etc. This initiative is useful in understanding how changes occurred in many benchmarking areas between 2004 and 2006.

CoP list

The following CoPs were chartered by the US nuclear industry between 2000 and 2005:

Configuration management benchmarking group

The configuration management benchmarking group CoP began as a networking group in 1994 on the initiative of PPL Corp (now PPL Susquehanna, LLC). This group established a working relationship with the Nuclear Records Management Association (NIRMA) and some CMBG members participated with NIRMA in development of ANSI/NIRMA CM 1.0-2000 (see Ref. [11]). Until this time there was not complete industry agreement for what constituted ‘Configuration Management’ and INPO AP-929, Rev.0 (see Ref. [23]) was entitled Configuration Control. Following completion of the NEI Configuration Control Benchmarking Project and knowledge transfer workshop, the industry began to see how configuration management could be improved. When the CMBG became the CoP, NEI revised the SNPM configuration control process to become configuration management in alignment with the ANSI/NIRMA standard. Then the CMBG worked with INPO to revise the subject process description. In 2005, INPO issued AP-929, Rev.1, (see Ref. [24]) Configuration Management Process Description.

Equipment reliability working group

Equipment reliability became an important industry focus area about 1998, when INPO began to see adverse trends in system unplanned capability loss factor. The NEI Equipment Reliability Benchmarking Project was conducted in 2002 to help facilitate the knowledge transfer process. The project was created by mutual agreement of NEI, INPO and EPRI when it became clear that process improvement and identification of best practices in this area was necessary to address an adverse trend of systems availability at many US plants. INPO had issued AP- 913 Rev.1 Equipment Reliability Process Description, and about one-third of all plants had performed some sort of implementation. Another one-third had begun implementing in 2002 and the final third had not yet started. This was therefore decided to be a good time to conduct the project. The Equipment Reliability Working Group (ERWG) was created a few months following the knowledge transfer workshop.

Nuclear supply chain strategic leadership (NSCSL, CoP)

The NSCSL was created in 2000 following the completion of the Materials and Services Benchmarking Workshop. At the workshop, a guest speaker from NUSMG (see Section 3.5.1 below) had spoken of the benefits of an organization focused on process management of each SNPM area, using IT as the example. NEI also pointed out that there was a lack of nuclear supply chain focus at the industry level because there were several small and disconnected SIGs tapping into industry manpower for networking purposes but these groups were collectively ineffective in managing the overall business aspects of the supply chain. An industry process description was authored by a team at INPO in about 1996 but industry managers said it did not reflect current supply chain best practices and it was not actively used by the industry as a whole. An effective supply chain was also required to be a key support element of the work management process. Improvements in the work management process were continuing to the point where the supply chain process was viewed as the next essential capability for success.

Nuclear information technology strategic leadership (CoP)

The Nuclear Utility Software Management Group (NUSMG) began operating in the 1980s as a networking forum for IT professionals. NUSMG members were for the most part software quality practitioners and IT managers. As the ‘Y2K Issue’ approached, NEI successfully tapped the knowledge and infrastructure of NUSMG to assist the industry address the Y2K issue. That success further encouraged NUSMG to be involved with the NEI benchmarking programme. Also about 1998 INPO began hosting an annual meeting for IT managers where issues could also be discussed. NUSMG began considering the benefits of functioning as a CoP at the NEI/NUSMG IT Benchmarking Workshop in 2000. About the same time utility IT managers approached NEI about creating a CoP for the IT Process. IT management thought it was beneficial to remain connected with INPO, but at the same time, they wanted to be able to meet as often as required to discuss issues. They were also interested in conducting more formal benchmarking as well as specific annual improvement projects. Their vision was also to maintain an alignment with INPO, NUSMG and the SNPM. In 2001, with the assistance of INPO, NEI chartered NITSL as the CoP for process SS001.

Nuclear asset management CoP

The NAM CoP evolved in several steps beginning with EUCG in 1997. Most nuclear business managers attended EUCG and many also served as NEI economic points of contact. Since 1989, the EUCG functional cost survey had provided useful information of comparison of costs. When the SNPM was issued in 1998, EUCG began collected activity base costing data as well as SNPM KPIs. In 1999, NEI conducted the Business Services Benchmarking Project as well as initiating a new ‘NEI Business Forum’ to meet the increasing needs for discussion and industry issue activity related to deregulation, plant sales, power uprates and regulatory issues such as decommissioning costs and environmental discussions about ‘Clean air credits’. As a result NEI created a nuclear asset management task force. Initially meetings were held concurrent with EUCG. Later separate meetings were required to address NAM TF project work. Finally NAM became an NEI-sponsored CoP. In 2005, the NAM CoP was initially assigned to remain with NEI but later in 2006 it was transferred to EPRI.

Nuclear information management strategic leadership (CoP)

After seeing the results attained by other CoPs, subject matter experts (SME) in the records management process were eager to conduct an NEI benchmarking project. Most were members of NIRMA and several were part of another networking group called Document Control and Records Management. Following completion of the benchmarking project a core group of SMEs arranged with NIRMA to organize NIMSL as an NEI-sponsored CoP. NIMSL CoP is the leadership team responsible for serving as a focal point for nuclear information management activities associated with the SNPM Process SS003. Information management includes records management, document control, procedures, and office services activities. NIMSL CoP enables plants to compare their methods to others to determine efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Nuclear human resources group (CoP)

Prior to 1994, industry nuclear human resource services were available from Edison Electric Institute (EEI). In 1994, a core group of nuclear human resource professionals met to discuss fitness for duty and staffing issues in the nuclear industry. The group found it easier to create a networking and shared services group called nuclear human resources professionals (NHRP) that was later formed under EEI as a Working Committee. NHRP accomplishments included implementing the NRC Fitness for Duty Rule and benchmarking other nuclear fingerprinting, professional development, recruiting and staffing and other similar human resources and compensation/labor issues. When the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) was formed, the human resource committee was not ‘transferred’ to NEI. About the same time, INPO was monitoring and analysing total nuclear industry staffing capabilities according to a standard set of accepted professional categories. Prior to this, the utilities relied upon private consulting companies to conduct periodic NPP staffing surveys. In 1996, INPO stopped collection and analysis of staffing data which gave the Electric utility cost group (EUCG) an opportunity to add staffing data to their services offerings. A functional staffing survey was created within the EUCG in 1997. Also in 1996, the NHRP was formed outside of EEI that no longer supported nuclear efforts or committees due to the formation of NEI. The Nuclear human resource group (NHRG) was facilitated by a human resources consultant with former nuclear utility experience. In 1999, NEI began briefing the NHRP about the benefits of conducting formal benchmarking and also in working with the EUCG to establish an improved standard nuclear staffing survey and HR metrics that were in alignment with the SNPM. These planning efforts resulted in the conduct of the NEI Human Resources Benchmarking Project in 2000. After the project was complete NHRP reorganized with executive sponsorship and a more senior leadership structure to become the NHRG (CoP).

Licensing community (CoP)

NEI began about 2000 to engage the NRC strategically with a group called the License amendment task force. Both NEI and the NRC each had their own LATF and there were joint meetings conducted periodically. NEI also began conducting Licensing Information Forums in the fall about six months prior to the next NRC Regulatory Information Conference. In 2002, the NEI LATF sponsored the Licensing Benchmarking project and the industry began to engage the NRC is mutually beneficial process issues as well as the traditional regulatory discussions. Following the NEI Licensing Benchmarking Project, the formation of a Licensing CoP was discussed as part of the workshop. The following year the group was referred to as the Licensing Community and the utility portion of the LATF began to serve as a steering body for the community.

Fire protection (CoP)

The fire protection CoP was created following completion of the NEI Fire Protection Benchmarking Project and accepted in principle at the NEI Fire Protection Information Forum in 2002. This group continues to evolve as a global CoP with over 125 members spanning US and International utilities as well as other fire protection organizations. Global reach is accomplished primarily via a highly effective Web-site however direct international contacts are also maintained by formal peer visits contact and meetings at the annual Fire Protection Forum.

Work Management Working Group

The INPO Work Management Working Group is long-standing organization that over the years has acted to create and improve the work management process, develop and update AP-928, the Work Management Process Description and also to facilitate discussions between work management professionals and other utility staff such as maintenance managers, outage managers and maintenance planning managers. Work management is the centerpiece of the SNPM due to the amount of resources required to maintain plant equipment, the importance of limiting maintenance back-log and the number of process interfaces required for efficient operation. INPO has long recognized this and by 2000 the early series of four sub-process AP-documents had all been consolidated into AP-928, Rev.0. At this point, the WMWG developed a White Paper about the advantages of being better ‘Asset managers’. By collaborating with NEI, the NEI work management role in Nuclear Asset Management Benchmarking Project was completed in 2003. The WMWG also issued Rev.1 to AP-928 and was recognized as the WM CoP. In 2007, the WMWG released AP-928, Rev.2.

CoP benchmarking methods

‘Benchmarking’ activities carried out by each CoP varied from group to group. Each group was characterized by a charter, leadership structure and membership requirements. All CoPs had access to at least one Web-site for communications, posting of information and conducting business. A wide variety of CoP benchmarking activities are summarized in Table 4 below. Each CoP may choose what type of activities are best to perform based on the maturity of the overall process, industry issues that may be challenging the process and the amount of resources they have available to conduct their business.

Source: Process oriented knowledge management

References

[8] Wenger, E., McDermott, R., Snyder, W., M., Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide To Managing Knowledge, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, USA (2002).